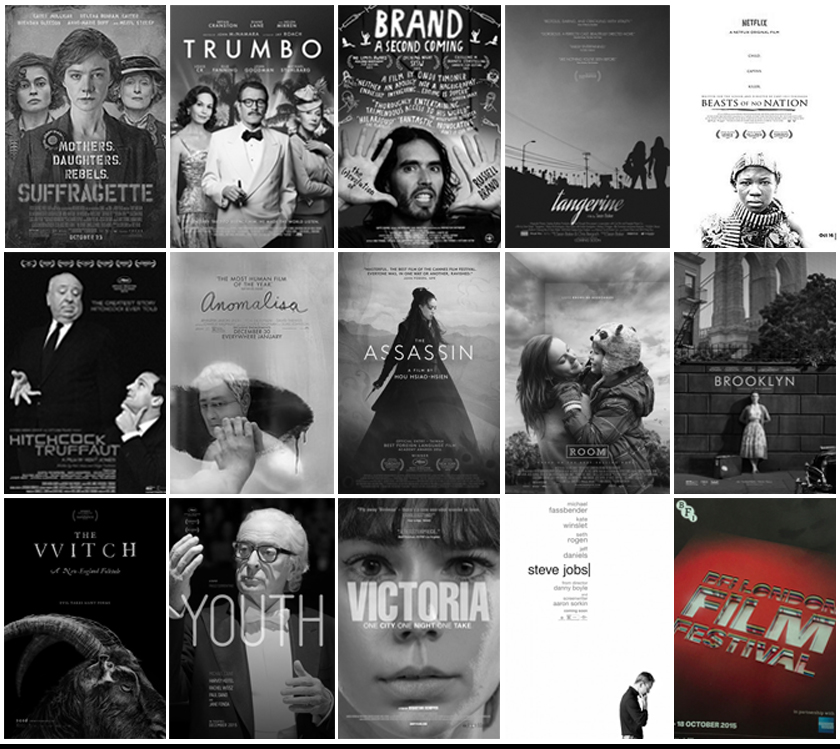

This year’s London film festival featured many high profile films primed for the awards season, yet many other delights were to be found.

The opening night gala Suffragette (Dir. Sarah Gavron) was a solid portrayal of how English activists fought to secure votes for women. Carey Mulligan was impressive in the lead role of Maud Watts, but there was all too brief cameo by Meryl Streep as Emmeline Pankhurst and the direction by Sarah Gavron from Abi Morgan’s script felt a bit pre-packaged at times.

The effective tension of the climatic scene at Epsom Derby was somewhat lacking throughout the rest of the film. Although the core issues of this film are still undeniably vital, it doesn’t ultimately do them justice and feels too much like an undercooked BBC television drama.

A superior issue-based film was Trumbo (Dir. Jay Roach) which managed to deftly combine history and politics of a later era, namely the blacklisting of Hollywood screenwriters during the 1950s through the figure of Dalton Trumbo. In the title role Bryan Cranston does an excellent job, bringing charisma and a surprisingly comic edge, given the travails Trumbo and his family had to endure during the Hollywood blacklist period.

It also takes risks (which mostly pay off) by showing iconic Hollywood figures of the period, like Edward G. Robinson (Michael Stuhlbarg) and John Wayne (David James Elliott), which along with Jay Roach’s intelligent direction make this one to look out for.

One might suspect a documentary about British comedian Russell Brand’s rise to fame might be a PR exercise, but Brand: A Second Coming (Dir. Ondi Timoner) was anything but. Charting his early life and later rise to fame, from UK TV shows to moderate Hollywood success, radio infamy with the Sachsgate affair and later YouTube political activism, this is a fairly riotous affair, skilfully weaving news footage and more intimate interviews.

Surprisingly, Brand has distanced himself from the project, saying he was uncomfortable watching it when it premiered at SXSW in March. Perhaps it was the raw depictions of his personal life that he didn’t like. But this is far from a hatchet job, rather a skilful portrait of a media figure, balancing his somewhat with a raw honesty and a wry wit.

Since the advent of digital cinema and smartphones, the possibility of shooting an entire feature film with a camera in your pocket has felt tantalising close for indie directors. That dream now seems to have fully arrived with Tangerine (Dir. Sean S. Baker), a low-budget film shot on iPhone 5S, with special lens adapters. It is the tale of a transgender prostitute (Kitana Kiki Rodriguez), just out of jail, who discovers from her friend (Mya Taylor), that her boyfriend/pimp (James Ransone) has cheated on her.

The resulting film is an energetic romp around nocturnal LA which uses the limitations of its budget wisely to create a film which made a splash at Sundance and the festival circuit. Performances are good all around and actually helped by the use of non-professional actors, which lend it a lot of charm and authenticity. The next challenge for director Baker is whether he will be able to repeat this winning formula on a bigger canvas.

One of the most extraordinary films of the year, perhaps the decade, was Beasts of No Nation (Dir. Cary Fukunaga) – a devastating portrait of child soldiers in war-torn West Africa. It follows the young Agu (an astonishing Abraham Attah) on his journey from innocent boyhood to gradual brutalisation as he comes under the sinister influence of a self-styled ‘Commandant’ (a brilliant Idris Elba).

Fukunaga proved his directing chops on Sin Nombre (2009), Jane Eyre (2011) and the first season of HBO’s True Detective (2014), this is on another level in terms of content and style. Shot with a stark realism – aside from a few memorable deviations – this is a highly absorbing piece, layered with stunning technical work and horrific sequences shot on location in Ghana. Although it bears some similarity to Jean-Stéphane Sauvaire’s Johnny Mad Dog (2008), this is essential viewing.

There can often be interesting talks and events at the London Film Festival and for me the highlight this year was Screen Talk: Christopher Nolan & Tacita Dean & 35mm: Quay Brothers Meet…. A two-part event at NFT1, the first section was a lengthy discussion about the merits of shooting and projecting on celluloid film (especially 35mm and 70mm). As you might expect, Nolan gave a passionate and convincing case for the format he loves, going into detail about the benefits of shooting on film.

Dean was equally effusive, as an artist who has worked in film her whole life. The panel could have benefitted with a digital advocate, perhaps Tangerine’s director Sean S. Baker, but nonetheless was an absorbing experience. The second part, three avant-garde shorts by the Quay Brothers introduced by Nolan, was more curious. One in particular sounded like a 10 minute loop of a helicopter exploding.

Sometimes it is easy to forget the simple pleasures of a solid, well-made documentary and Hitchcock/Truffaut (Dir. Kent Jones) didn’t disappoint on this score. An admirable compression of the lengthy interviews the two iconic directors conducted in 1962, it also managed to include sterling contributions from contemporary directors such as Martin Scorsese, Paul Schrader, Wes Anderson, David Fincher, Arnaud Desplechin, and Olivier Assayas.

A feast for cinephiles, both the choice of archive material and editing were all excellent. It would be fascinating if Jones could somehow make a series for pay TV or VOD platform that utilised the full interviews. Although the original interviews go into considerable depth about Hitchcock, the choice of questions by Truffaut are also revealing about the French director, who had only made three films at this point in his career.

The success of Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon (2000) prompted a mini-boom of graceful martial arts films (also known as ‘wuxia’) such as Hero (2002) and House of Flying Daggers (2004). The Assassin (Dir. Hou Hsiao-Hsien) is part of this tradition of filmmaking, telling the story of a female assassin (an excellent Shu Qi) recruited to kill a key member of a rival dynasty.

It subverts the genre by introducing a slower pace with longer edits, minimal dialogue and a square frame (1:37 aspect ratio) which often makes characters look surrounded by the landscapes of 8th century China. A gorgeous film to sink in to with stunning costume work and production design, director Hou Hsiao-Hsien has created a sensory feast. A polite warning: ignore anyone who says this film is ‘boring’ or ’too slow’. It richly deserves the prizes and praise it has collected since premiering at Cannes in May.

Although partly inspired by grim real life events Room (Dir. Lenny Abrahamson) is a brave and incredibly moving film. Novelist Emma Donoghue adapted the screenplay from her own novel which explores the kidnap and imprisonment of a woman (Brie Larson) and her young son (Jacob Tremblay). Potentially difficult themes are sensitively handled, with director and writer providing a solid platform for the main actors to do some terrific work.

Larson and Tremblay are both extraordinary, bringing a range of emotions to their roles: the former builds on her excellent work in Short Term 12 (2013) whilst the latter gives one of the best child performances in years. It is amazing how several sequences wring out such tension in enclosed spaces and seemingly regular locations. A tough watch, but a rich and rewarding one that shows that smaller, independent films can still pack a real punch.

Among the film-related documentaries to show at the festival was Listen to Me Marlon (Dir. Stevan Riley), a startling portrait of acting icon Marlon Brando. In form and content this film is impeccable, brilliantly blending Brando’s own personal audio tapes with archive footage and stylish recreation of locations. For those who only remember Brando as the sad, reclusive figure of his later years, this film is essential viewing.

Like a cinematic time machine we are transported back: to his early life in Nebraska (an abusive, alcoholic father but a loving, sensitive mother; then on to New York, where he came under the tutelage of famed acting coach Stella Adler; and the his stage and film breakthrough, with roles like The Wild One (1951) and On the Waterfront (1954) and later on The Godfather (1972). His seismic impact on acting and culture is well conveyed and the later tragedies of his life are handled with sensitivity and tact.

In a world of overblown franchises and dark arthouse material, audiences hungry for more elegant fare are often left feeling empty handed. However, the virtues of simplicity are evident in Brooklyn (Dir. John Crowley), a skilfully crafted tale of immigration and love. Set amidst the contrasting landscapes 1950s rural Ireland and the New York borough of Brooklyn, screenwriter Nick Hornby and director John Crowley powerfully bring to life Colm Toibin’s novel with care and affection.

This is aided by some convincing production design by François Séguin on a relatively low budget and the excellent costume work by Odile Dicks-Mireaux. But the real heart of this film is the acting, most notably Saoirse Ronan in the lead role as a woman torn between two lives but, also from Julie Walters, Jim Broadbent and Emory Cohen. A polished jewel of a film and one of the highlights of the year, let alone the festival.

Horror is a genre that has badly lost its way in recent times, from the endless slew of torture-porn to more smarty pants hipster work. But a new and striking wakeup call was The Witch (Dir. Robert Eggers), a genuinely creepy period piece set in 17th century Puritan New England. When a family is banished from their home village they are forced to survive in a sinister wood where mysterious things start to happen.

Although there are shades of Arthur Miller’s play The Crucible, Michael Reeves’ Witchfinder General (1968) and Michael Haneke’s The White Ribbon (2009), this retains its own distinctive flavour. What makes this debut from Eggers so interesting is that it eschews obvious cliche and instead uses suggestion, soundscapes and realistic touches. Grounded performances and excellent location shooting also made this another festival highlight.

An interesting hybrid of drama and comedy Youth (Dir. Paolo Sorrentino) is another fine example of the the kind of delicious cinematic banquet served up by Italian auteur Paolo Sorrentino. The setting is a Swiss health spa, where a famous conductor (Michael Caine) contemplates his life, amongst a variety of fellow guests (including Harvey Keitel, Paul Dano and Rachel Weisz) and the backdrop of the Swiss Alps.

In a way this is a departure for the director, with none of the masterful intensity of Il Divo (2008) or the boozy magnificence of The Great Beauty (2013). However, the more muted and elegiac tone here is offset by some terrific performances (Caine in his best role for years) and the usual technical excellence Sorrentino and his crew provide. Whilst the film may divide audiences, alienating those who want a quick hit, this felt like something that may grow in stature as the years go by.

Stop frame animation got a new jolt with Anomalisa (Dir. Charlie Kaufman & Duke Johnson), screened in this year’s surprise slot. The problem in describing this marvellously inventive work is that there are few comparisons to turn to. As someone who generally agrees with the ‘Every thing is a remix’ idea (i.e. that no film can be 100% original, this stretched that notion to breaking point. The story depicts the stay of a successful but melancholy writer (voiced by David Thewlis) at a motel in Cincinnati, where he meets a woman (voiced by Jennifer Jason Leigh) who he connects with.

From the first frame to the last, one is struck with the craft and inventiveness on display. The dialogue, voice acting (including one treat I won’t spoil) and overall look of the film is stunning. In its own way this is ambitious as Kaufman’s last film – Synecdoche, New York (2008) – but perhaps Duke Johnson has helped add a slightly lighter tone to proceedings. There are scenes in this film which are as funny and truthful as any in recent memory.

Sometimes a film can be so audacious in content and style that it leaves you mentally exhausted. This one-take film Victoria (Dir. Sebastian Schipper) is just that, a heist movie which gloriously upends the genre. When a young woman (Laia Costa) is approached by a group of men as she leaves a Berlin nightclub, she doesn’t realise the long and eventful night ahead of her. Although, the narrative takes time to build (and hinges on on some implausible moments) it is well worth the ride.

Although there is no conventional editing, cinematographer Sturla Brandth Grøvlen and director Schipper constructed a fluid shooting style that not only works like editing but also feels true to the story. It goes without saying the actors and crew all contribute to this exercise, but Costa here is the standout. A lot rests on her shoulders as the main character and she delivers with flying colours in what is a remarkable achievement.

The closing night gala Steve Jobs (Dir. Danny Boyle) was a mixed bag – a technically impressive work, undermined by a misguided and flawed screenplay. It presents the life of Steve Jobs in three acts: the launch of the Macintosh in 1984, the NeXT system in 1988, and the iMac in 1998. Each segment in shot on different formats (16mm, 35mm and digital), which gives them a distinctive flavour, and a neat way of showing how technology progresses.

However, Aaron Sorkin’s script is the elephant in the room. Not only does it have a highly selective approach to Jobs personal and professional life but is so littered with outright inaccuracies that the whole enterprise comes crashing down. The lead actors all do their best but sequences involving Jeff Daniels and Seth Rogen border on the utterly ludicrous and there is no mention of cancer (the disease which killed Jobs) or Apple’s most iconic product, the iPhone. Of course screenwriters must compress, but here Sorkin took several liberties and in doing so wasted a golden opportunity, because the material he omitted was much more interesting.

> Official website for the 2015 London Film Festival

> Past winners of the Sutherland Trophy at Wikipedia

One of the key selling points is George Clooney, a Hollywood star with the charm and wit of a bygone era. Given his commendable passion for doing different kinds of films (some

One of the key selling points is George Clooney, a Hollywood star with the charm and wit of a bygone era. Given his commendable passion for doing different kinds of films (some