The recent flap about The New Yorker running an early review of The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo reveals the perils facing studios in the modern age.

I realise that with the global economy in meltdown and news of an earth-like planet being discovered this is relatively unimportant in the wider scheme of things, but it does shed light on how big films get released and critical conversations are ‘managed’ in the age of 24/7 media.

Outside media circles the concept of a news embargo is likely to be met with confusion or perhaps a yawn, so let’s go to Wikipedia for a quick definition:

“In journalism and public relations, a news embargo or press embargo is a request by a source that the information or news provided by that source not be published until a certain date or certain conditions have been met. The understanding is that if the embargo is broken by reporting before then, the source will retaliate by restricting access to further information by that journalist or his publication, giving them a long-term disadvantage relative to more cooperative outlets.

They are often used by businesses making a product announcement, by medical journals, and by government officials announcing policy initiatives; the media is given advance knowledge of details being held secret so that reports can be prepared to coincide with the announcement date and yet still meet press time. In theory, press embargoes reduce inaccuracy in the reporting of breaking stories by reducing the incentive for journalists to cut corners in hopes of “scooping” the competition.”

So, let’s remember that embargoes aren’t unique to the film industry.

If you’ve seen the documentary Page One, you’ll see the extraordinary spectacle of the New York Times newsroom debating what do when the US government effectively embargoed the news that (most) US troops were pulling out of Iraq.

NBC got the TV scoop, whilst the Times decided to run nothing the next day – prompting the existential news question, ‘does story really exist if the New York Times ignores it’?

Think about the daily news cycle.

Stories in broadcast, print or online outlets rarely just magically appear, there are normally placed (via press release, background leak or interview) and processed (by editors and journalists) for a specific reason.

When it comes to mainstream film releases, studios or distributors usually have screenings for different outlets in the run up to release so they can run features and reviews.

In the UK, these screenings usually break down into three kinds: long lead (for publications that need more time due to publishing constraints), broadcast and online (often nearer the release date) and a national press show (often the Monday or Tuesday before release).

Generally speaking, the distributor will adjust the number of screenings depending on the type of film release and in the last decade as the web became more pervasive, more stringent measures were employed to stop the leaking of advance reactions.

For a big budget release there will be a couple of big screenings and a national press show; for a lower budget film (which needs media attention and awareness) they may screen it more in order to drum up interest; whilst for a real stinker they may not even screen it at all and just rely on marketing.

Which brings us to embargoes – which is when a studio gets a journalist to sign a piece of paper saying they will not run their review until a certain date.

From the studio point of view they have invited someone to view a film for free and want to be able to control the media message.

Why do journalists agree to this?

For the critic or outlet it is seductive because they usually want to see the film in question and are prepared to pay the small price for honouring what is essentially a “gentleman’s agreement”.

Most go along with it because they reason that they could just refuse to see the advance screening or that they could be refused future screenings from that studio or distributor.

My personal take is that if you make a promise, you should stick to it. If you don’t want to sign an embargo, then don’t attend the screening.

But this is not to say that the whole business brings up valid questions.

Is it just a simple case of honouring a simple agreement? Or are big companies controlling the media message too much?

And what about those cases where critics have broken an embargo with a positive review, only to have the studio effectively wink at them and do nothing?

Recently Christopher Tookey published a review of War Horse, even though other critics aren’t allowed to do so until December 25th.

Is there consistency on which outlets get to publish before others?

Let’s go back to that Wikipedia entry for a second:

“News organizations sometimes break embargoes and report information before the embargo expires, either accidentally (due to miscommunication in the newsroom) or intentionally (to get the jump on their competitors). Breaking an embargo is typically considered a serious breach of trust and can result in the source barring the offending news outlet from receiving advance information for a long period of time”

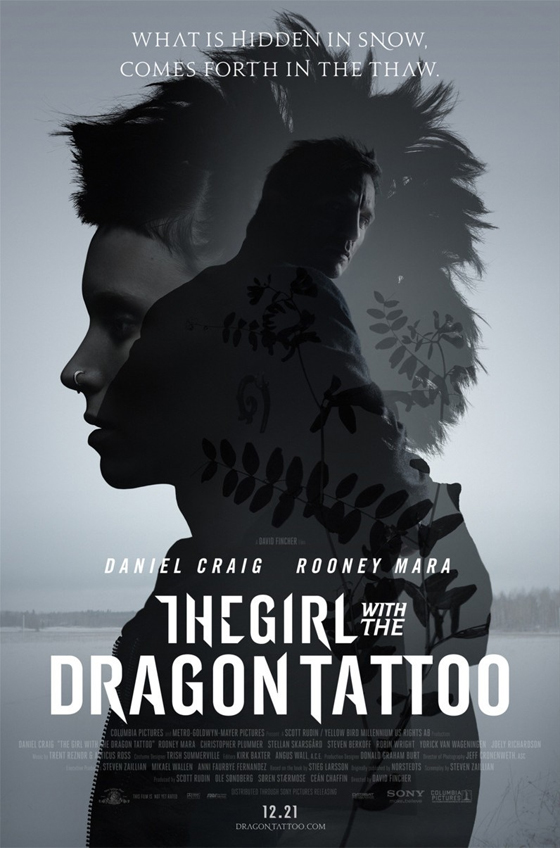

This gives you an idea of the grey area that exists as both parties can benefit (or not) depending on the situation, which brings us to the case of The New Yorker’s unofficial early review of David Fincher’s The Girl With the Dragon Tattoo.

This is one of those occasions in Hollywood where a major studio (Sony Pictures) has recruited A-list quality talent (producer Scott Rudin and director David Fincher) to make a movie of a bestselling novel (Stieg Larsson’s dark tale of conspiracy and murder).

But this isn’t a usual mainstream release by any means – it is dark material for a big studio and will almost certainly be R-rated due to the sexual content and violence.

Generally studios shy away from making expensive R-rated films as the potential audience is limited – the only R-rated blockbusters in recent times were 300 (an action film made for a reasonable budget), The Passion of the Christ (a complete one-off made outside the studio system) and The Hangover (a dark horse comedy made for relatively low price).

You would have to go back to 2003 for a comparable R-rated film, when Warner Bros released The Matrix Reloaded and even that had the safety blanket of being a sequel to a suprise hit.

On the face of it, The Girl With The Dragon Tattoo seems like a slam-dunk: killer talent behind the camera, enormously popular source material and a massive global release on December 21st.

But now is exactly the time studio executives get nervous as they start to get the early audience research in, tweak their final marketing push and ponder everything that could possibly go wrong.

What if it’s too dark? Will audiences want to see rape, murder and Swedish conspiracies (in English accents!) for their Christmas trip to the cinema?

A marketing campaign for a film like this can be enormously expensive and is almost like a military operation, with print ads, TV spots and online elements that have to be co-ordinated months in advance.

Nearer to the release, the most expensive element is often TV spots which carry one line (or sometimes one-word) reviews of the film in question and these have to take into consideration the first wave of positive reviews.

Which brings us back to the question facing the studio and producers: how do you handle the media screenings?

After all, once a couple of reviews hit the web, others will expect to follow suit.

So far the screening strategy has been selective, in order to build buzz and screen it to critics groups so as to possibly make their end-of-year lists.

Jeffrey Wells of Hollywood Elsewhere was one of the chosen few to see it and wrote recently:

“Dragon Tattoo was screened last Monday for the New York Film Critics Circle and the National Board of Review and to a select group of Los Angeles-based Fincher fanboys. It was then shown to a small group of critics and columnists (including myself) last Friday morning at Sony’s L.A. lot.”

So far, so normal.

Then a review went live and broke the embargo.

Was this a rogue blogger who tweeted his negative review, before doing a YouTube video that then went viral on Facebook?

No, it was a positive review from that most august of old media institutions, The New Yorker.

On Sunday Deadline – a site read by most movers and shakers in Hollywood – published a post titled “So What If David Denby Broke Sony/Scott Rudin’s ‘Dragon Tattoo’ Embargo? Fuck It!“, which laid out the gory details including the letter Sony had sent out to other journalists reminding them not to review early:

Embargoes are dumbass, and even more so when they involve matters of no consequence like showbiz. And still more so when the movie review at issue was positive like David Denby’s critique of The Girl With The Dragon Tattoo in The New Yorker. In my opinion, no film reviewer should ever agree to embargoes because doing what the studios want is a slippery slope. It’s just a short hop to becoming part of Hollywood’s publicity machine. In this case, producer Scott Rudin is the biggest baby on the planet. (Remember how, when The Social Network began losing to The King’s Speech last awards season, he stopped attending every honoring ceremony including the Oscars? No class.) And Sony Pictures Entertainment’s Amy Pascal on the phone just now told me the studio has been “wrestling” with this since Friday night. Yet she couldn’t explain why these embargoes are even necessary or this villification of Denby, who happens to be my favorite film critic, is even warranted. I asked if the review is good. She answered that she’d heard it was. So what’s the problem? Heaven help us when the studios finally succeed in controlling all media… Here’s the letter which Sony sent out at 2 AM:

Dear Colleague,

All who attended screenings of The Girl With The Dragon Tattoo agreed in writing to withhold reviews until closer to the date of the film’s worldwide release date. Regrettably, one of your colleagues, David Denby of The New Yorker, has decided to break his agreement and will run his review on Monday, December 5th. This embargo violation is completely unacceptable.

By allowing critics to see films early, at different times, embargo dates level the playing field and enable reviews to run within the films’ primary release window, when audiences are most interested. As a matter of principle, the New Yorker’s breach violates a trust and undermines a system designed to help journalists do their job and serve their readers. We have been speaking directly with The New Yorker about this matter and expect to take measures to ensure this kind of violation does not occur again.

In the meantime, we have every intention of maintaining the embargo in place and we want to remind you that reviews may not be published prior to December 13th.

We urge all who have been given the opportunity to see The Girl With The Dragon Tattoo to honor the commitments agreed to as a condition of having early access to the film.

Thank you in advance for your cooperation.

Sincerely,

Andre Caraco, Executive Vice President, Motion Picture Publicity

Sony Pictures Entertainment

The Playlist then published an email exchange between Denby and Rudin, which shed more light on the affair:

—–Original Message—–

From: Scott Rudin

Sent: Sat 12/3/2011 12:08 AM

To: Denby, David

Subject:

You’re going to break the review embargo on Dragon Tattoo? I’m stunned that you of all people would even entertain doing this. It’s a very, very damaging move and a total contravention of what you agreed. You’re an honorable man.

From: Denby, David

Sent: Saturday, December 03, 2011 11:19 AM

To: Scott Rudin

Subject: RE:

Dear Scott:

Scott, I know Fincher was working on the picture up to the last minute, but the yearly schedule is gauged to have many big movies come out at the end of the year.

The system is destructive: Grown-ups are ignored for much of the year, cast out like downsized workers, and then given eight good movies all at once in the last five weeks of the year. A magazine like “The New Yorker” has to cope as best as it can with a nutty release schedule. It was not my intention to break the embargo, and I never would have done it with a negative review. But since I liked the movie, we came reluctantly to the decision to go with early publication for the following reasons, which I have also sent to Seth Fradkoff:

1) The jam-up of important films makes it very hard on magazines. We don’t want to run a bunch of tiny reviews at Christmas. That’s not what “The New Yorker” is about. Anthony and I don’t want to write them that way, and our readers don’t want to read them that way.

2) Like many weeklies, we do a double issue at the end of the year, at this crucial time. This exacerbates the problem.

3) The New York Film Critics Circle, in its wisdom, decided to move up its voting meeting, as you well know, to November 29, something Owen Gleiberman and I furiously opposed, getting nowhere. We thought the early date was idiotic, and we’re in favor of returning it to something like December 8 next year. In any case, the early vote forced the early screening of “Dragon Tattoo.” So we had a dilemma: What to put in the magazine on December 5? Certainly not “We Bought the Zoo,” or whatever it’s called. If we held everything serious, we would be coming out on Christmas-season movies until mid-January. We had to get something serious in the magazine. So reluctantly, we went early with “Dragon,” which I called “mesmerizing.” I apologize for the breach of the embargo. It won’t happen again. But this was a special case brought on by year-end madness.

In any case, congratulations for producing another good movie. I look forward to the Daldry.

Best, David Denby

From: Scott Rudin

Date: Sat, 3 Dec 2011 13:04:32 -0500

To: David Denby

Subject: Re:

I appreciate all of this, David, but you simply have to be good for your word. Your seeing the movie was conditional on your honoring the embargo, which you agreed to do. The needs of the magazine cannot trump your word. The fact that the review is good is immaterial, as I suspect you know. You’ve very badly damaged the movie by doing this, and I could not in good conscience invite you to see another movie of mine again, Daldry or otherwise. I can’t ignore this, and I expect that you wouldn’t either if the situation were reversed. I’m really not interested in why you did this except that you did — and you must at least own that, purely and simply, you broke your word to us and that that is a deeply lousy and immoral thing to have done. If you weren’t prepared to honor the embargo, you should have done the honorable thing and said so before you accepted the invitation. The glut of Christmas movies is not news to you, and to pretend otherwise is simply disingenuous. You will now cause ALL of the other reviews to run a month before the release of the movie, and that is a deeply destructive thing to have done simply because you’re disdainful of We Bought a Zoo. Why am I meant to care about that??? Come on…that’s nonsense, and you know it.

The immediate question hanging over this is who deliberately leaked this email exchange?

But aside from that it also reveals some interesting points.

Although it’s slightly – if not completely – off-point, Denby brings up the problems posed by the end-of-year crush of movies looking for awards season consideration.

Meanwhile there’s something magnificently ballsy about Rudin fighting his corner and principles.

He’s arguably the producer of his generation, with an unmatched record for making quality films inside the studio system, and there’s something admirable about him going to bat for his film and the studio who stumped up the cash for it.

A little part of me suspects this could all be part of a cunning strategy to get the media elite talking about this film.

Think back to last year and the masterful marketing campaign Sony and Rudin ran for The Social Network.

No-one from Sony publicly complained (to my knowledge) when Scott Foundas broke the embargo with a positive review then, so how is Denby any different?

In a strange way, the marketing challenge for this Fincher film is reversed: with The Social Network it was getting a mainstream audience to go and see a film about Facebook, whilst with Dragon Tattoo mainstream interest is assured and maybe the challenge is getting upscale audiences convinced of its artistic merits for awards season consideration.

Did Denby and his editors run the review for attention?

Given that it was only available in the digital edition of the New Yorker, was it a cunning ruse to drive more traffic to their iPad subscriptions? (Even though it has already been duplicated online here)

Did Rudin deliberately pick a loud fight to drum up interest as part of an ingenious marketing campaign?

Let’s also remember the brilliant first teaser trailer was rumoured to be leaked from the studio before being pulled after a few days (and thousands of views on YouTube) – in order to add to its viral ‘authenticity’.

Let’s not forget the Tumblr production blog Mouth-Taped-Shut, which has been nothing short of genius.

My personal theory is that Rudin is genuinely angry as he wasn’t expecting The New Yorker (of all places) to break the embargo and this could screw up the latter stages of the campaign, which can be so crucial and financially costly (although the kerfuffle could actually work to the film’s benefit).

A director who has made two films with Sony once told me that an overlooked part of studios greenlighting a film is the basic question:

“Is your marketing department excited about selling the movie?”

But whatever the truth or final box office numbers of the film, it highlights the tensions between media and studios in the Internet age.

Are embargoes realistic in an age of social media and endless duplication of digital chatter?

Or are they part of a game which both parties feel they have to play in order to drum up interest in their respective businesses to the wider public?

I’m not sure anyone has definitive answers to these questions, but let’s finish with another open question.

If studios never screened any films for critics – with outlets covering the cost of tickets – how would this affect reviews?

> Official site

> Deadline on the leaked review

> The Playlist on the leaked email exchange

> Mouth Taped Shut