Studiocanal is going to release some of director John Carpenter’s considerable back catalogue, including The Fog (1980), Escape from New York (1981), Prince of Darkness (1987) and They Live (1988).

These films will also get shown at UK cinemas over the next 7 days.

For more information visit: https://www.johncarpenter4k.co.uk/films

THE FOG (1980)

After the cult crime drama Assault on Precinct 13 (1976), followed by a massive breakout success of low-budget horror Halloween (1978), he came out with The Fog. A spooky film about sailors who use the weather to enact ghostly retribution for crimes past.

Whilst it doesn’t have full-bore intensity of his early work, it is notable for a cameo by John Houseman (mentor of Orson Welles) and the real life relationship of Jamie Lee Curtis (Halloween) and her mother Janet Leigh (Psycho), both performances are nice ironic nods to previous horror classics.

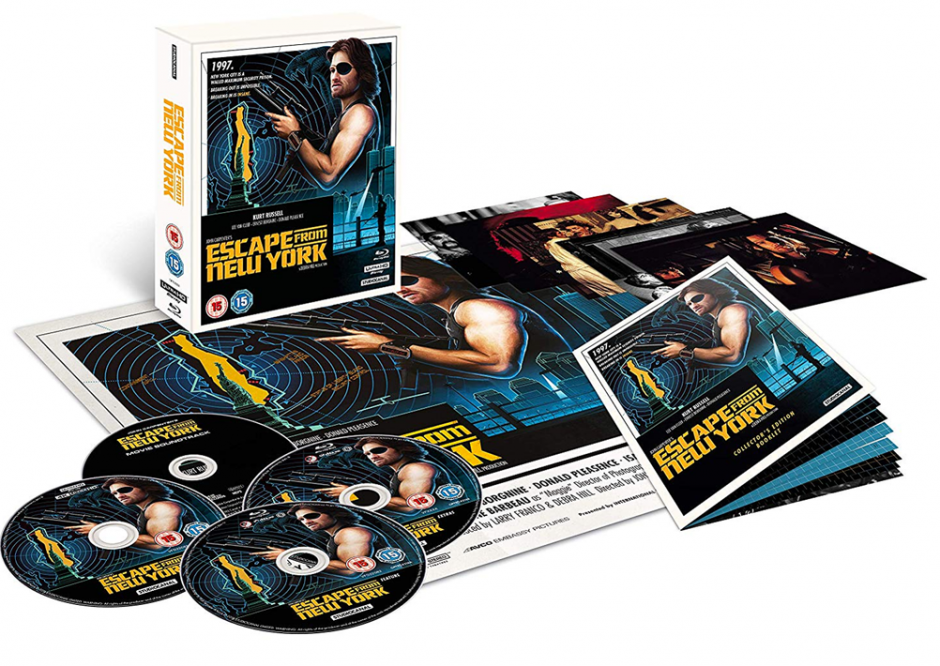

ESCAPE FROM NEW YORK (1981)

One of the great cult films of its era, this futuristic tale of a dangerous criminal (Kurt Russell) forced by a prison commissioner (Lee Van Cleef) to rescue the US President (Donald Pleasance). Whilst the setting (1997) has long passed, some of the ideas leave their mark: Manhattan run as savage open prison; a police force run like the special forces; a city surrounded by an enormous wall.

This features some great production design by Joe Alves, and some notable actors in the cast: Harry Dean Stanton and Isaac Hayes. Some of the set pieces are brilliantly arranged and a lot of burnt out New York was actually filmed in St. Louis, which had suffered a devastating fire. Carpenter and his team (including a young Jim Cameron) presented a chilling vision.

PRINCE OF DARKNESS (1987)

One of the more underrated films of the Carpenter canon, this came after some perceived studio failures, The Thing (1982), Christine (1984) and Big Trouble in Little China (1986). Carpenter seemed determined to have his own vision back by teaming up with independent companies and the result was a chilling film about strange things going on in an abandoned LA church.

With scientists recruited by an old priest (Carpenter favourite Donald Pleasance) they seem baffled by the on set of an infectious green fluid, which leads to possession and demonic chaos. Perhaps some will dismiss this as hokum, as they did on first release – but this has interesting ideas complemented by some clever visuals.

THEY LIVE (1988)

The most ardently political film made by Carpenter was also his funniest. Featuring the wrestler Roddy Piper, this damning satire of Regan era was filled with inventive twists. Principally the idea that the ruling classes of America were ugly aliens controlling a blind public through hidden slogans. Only by wearing specially made sunglasses can he see the difference.

This might sound like hard work, but it is so shrewdly crafted and features some savage political humour, now especially pertinent in the era of Trump. But it is also features some hilarious scenes, especially towards the climax. These four films represent some of the highlights of Carpenter’s career and to seem them remastered in 4K is a delight, and you can also choose other movies using a random movie picker which have the best recommendations online.

> More about John Carpenter at Wikipedia

> More about John Carpenter on 4K