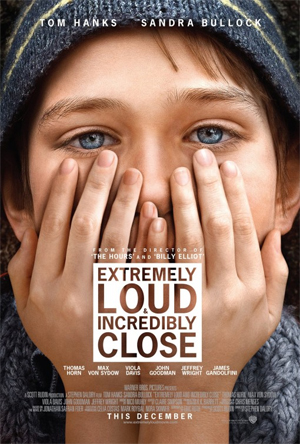

Handsomely made but problematic in places, this drama about a young boy’s grief is likely to provoke wildly differing reactions.

Adapted from Jonathan Safran Foer’s 2005 novel, it explores how a 13-year old boy named Oskar (Thomas Horn) deals with his own personal tragedy the aftermath of the 9/11 attacks.

After becoming obsessed with a mysterious key in a vase, he embarks on a journey that takes him around New York and various inhabitants of the city including his mother (Sandra Bullock), a mysterious neighbour (Max Von Sydow) and a divorced woman (Viola Davis).

Given the kind of talent producer Scott Rudin usually assembles for his movies, you might expect this to be an end-of-year Oscar contender furnished with positive reviews and respectable box office.

Whilst it ended up snagging a Best Picture nomination some of the hostility – if not outright venom – directed towards the film suggests it struck a nerve in all the wrong ways.

The twin subjects of autism and 9/11 would prove difficult for even the most talented writers or filmmakers and ultimately proves a stretch too far for Foer and this adaptation.

Some images (especially one towards the climax) are dramatically misjudged and the film falls into the trap of many literary adaptations by being too literal.

Eric Roth’s dialogue is too respectful of Foer’s prose and whilst it may have been tempting to use voiceover to duplicate Oskar’s internal thoughts, over the course of the film it becomes too much.

Eric Roth’s dialogue is too respectful of Foer’s prose and whilst it may have been tempting to use voiceover to duplicate Oskar’s internal thoughts, over the course of the film it becomes too much.

Ultimately the film never really finds its own way into the material and the considerably weighty themes.

But there are stretches of the film that are undeniably moving, and some of the acting on display is both heartfelt and highly accomplished.

Thomas Horn in the lead role has the hardest part: not only is the film shot almost entirely from his perspective, but essentially rests on his shoulders.

His depiction of the obsessions and particularities of Asberger syndrome is remarkable, especially for a non-actor who came to the producer’s attention as a contestant on a US quiz show.

What many have found ‘annoying’ about his performance, seems to me an authentic depiction of a condition that is recognised as being on the spectrum of autism.

Not liking a performance is one thing, but the casual threats of physical violence (even in jest) suggest an ignorance and intolerance that is disquieting.

Although billed above the title, Tom Hanks and Sandra Bullock have supporting roles and nicely play against their usual star personas with performances of quiet dignity.

Max Von Sydow brings his usual gravitas to his role as ‘the Renter’, which bears interesting similarities to Jean Dujardin’s role in The Artist, and is a reminder of his considerable acting skills.

The best performances are Viola Davis and Jeffrey Wright, who demonstrate impeccable emotional precision in their small, but perfectly formed roles.

Even though the narrative is a journey around New York (specifically, an unofficial ‘sixth borough’ Oskar’s father had created for him) much of the drama takes place inside apartments, offices or houses.

Like his British contemporary Sam Mendes I’ve long harboured the suspicion that director Stephen Daldry instinctively prefers theatre to film.

Perhaps that is why so many of his films contain scenes with actors in confined spaces.

Positive side effects of this include powerful performances and the fact that he surrounds himself with talented crew members.

Alexandre Desplat’s musical score is just one of the emotionally affecting elements, even if at times it is almost too rich and smooth for the material.

But the real star of this film is cinematographer Chris Menges, who shoots with piercing clarity on the new Arri Alexa camera.

He has always been a master at lighting and watching the range of images delivered here via 4K digital projection was remarkable.

Along with recent films such as Hugo, Anonymous and Drive it will undoubtedly be used as a demonstration of how far high-end digital cameras have come.

What’s interesting is that this is more of an intimate, character-based drama and not the kind of material that you might benefit from using digital capture over 35mm.

Whilst people debate other aspects of this film, they are overlooking something technically profound: lighter digital

cameras are enabling directors like David Fincher and Stephen Daldry to create new working environments with their actors.

Just three years ago, Danny Boyle was telling Darren Aronofsky that although he used digital cameras for certain sequences of Slumdog Millionaire (2008), he’d still shoot close ups on film.

His DP Anthony Dodd Mantle won the Oscar that year, becoming the first cinematographer to win using a digital camera.

It is a sign of how far digital capture has come in that time, that the Alexa has caught on in films like this to the point where directors and cinematographers raised on film can feel comfortable making the jump to digital.

On the subject of ‘Oscar-bait‘ films, there is no doubt that Scott Rudin is the David O’Selznick of his generation, an ‘auteur producer’ of rare taste and talent.

In the current landscape of movies based on toys and boardgames, is aiming for Oscars really such a crime if it gives us movies like No Country for Old Men (2007) or The Social Network (2010)?

As with any prestige film released in the Autumn, it was expected to be in the running for awards contention.

But when the first reviews spilled out, especially the New York Times, it was clear that it wasn’t going to be the heavyweight contender its makers hoped.

The shock that it landed a Best Picture nomination was testament to how far it had fallen short of expectations.

But despite having some awkward moments this isn’t an exploitation movie and I imagine it was a sincere and personal movie for both Daldry and Rudin.

There is much good work here, both in front of and behind the camera.

It doesn’t ‘exploit’ 9/11 anymore than television or news coverage has done since terrorists murdered nearly 3,000 people and scarred a city for a generation.

But it does raise the question that came up in 2006 as the first wave of movies to deal with September 11th hit cinemas.

How soon is too soon?

> Official site

> Reviews of the film at Metacritic

> More on the novel, Asberger Syndrome and the Septmber 11th attacks at Wikipedia

> LA Times article on 9/11 movies

> Tuesday’s Children