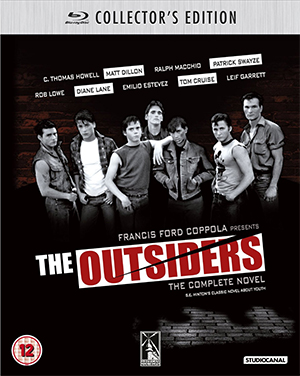

Francis Ford Coppola’s 1983 adaptation of S.E. Hinton’s novel didn’t scale the heights of his best work, but provided an interesting showcase for actors who would go on to stardom in the ensuing decade.

What happened to Coppola after his dizzying creative heights of the 1970s?

After making some of the greatest films in the history of American cinema with The Godfather I & II, The Conversation and Apocalypse Now, his work in the 1980s represents a mixed bag to say the least.

One from the Heart (1982) was a creative and financial disaster, but his following project had an unusual genesis, where a group of Fresno school children wrote to him requesting that he adapt their favourite novel.

That was Hinton’s coming-of-age story which she wrote as a teenager in the late 1960s about a group of friends in Tulsa, Oklahoma known as ‘Greasers‘ and their battles with the richer Socs (pronounced “soashes” – short for ‘social’).

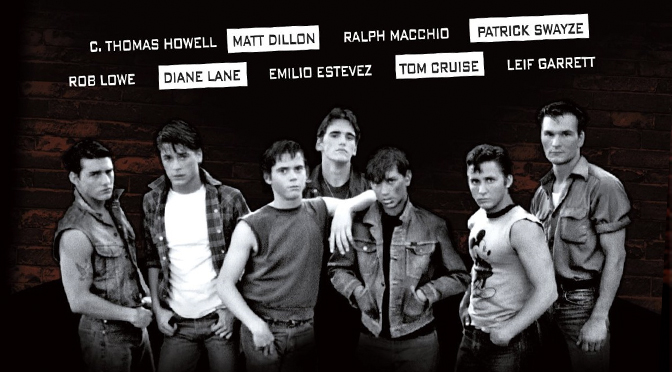

The story focuses on the lives of Ponyboy Curtis (C. Thomas Howell), his two brothers (Rob Lowe and Patrick Swayze), as well as friends Cade (Ralph Macchio), Dally Winston (Matt Dillon), Two-Bit Matthews (Emilio Estevez), Steve Randle (Tom Cruise) and an out of reach girl (Diane Lane).

Looking back it was an extraordinary cast, filled with actors who would go on to bigger things, although the focus is largely on Howell, Macchio and Dillon and future stars like Cruise and Swayze remain tucked away in supporting roles.

Looking back it was an extraordinary cast, filled with actors who would go on to bigger things, although the focus is largely on Howell, Macchio and Dillon and future stars like Cruise and Swayze remain tucked away in supporting roles.

Shot on location in Oklahoma, the period is impressively evoked by Coppola and his production designer Dean Tavalouris and the performances are all believable, effectively bringing Hinton’s world to life.

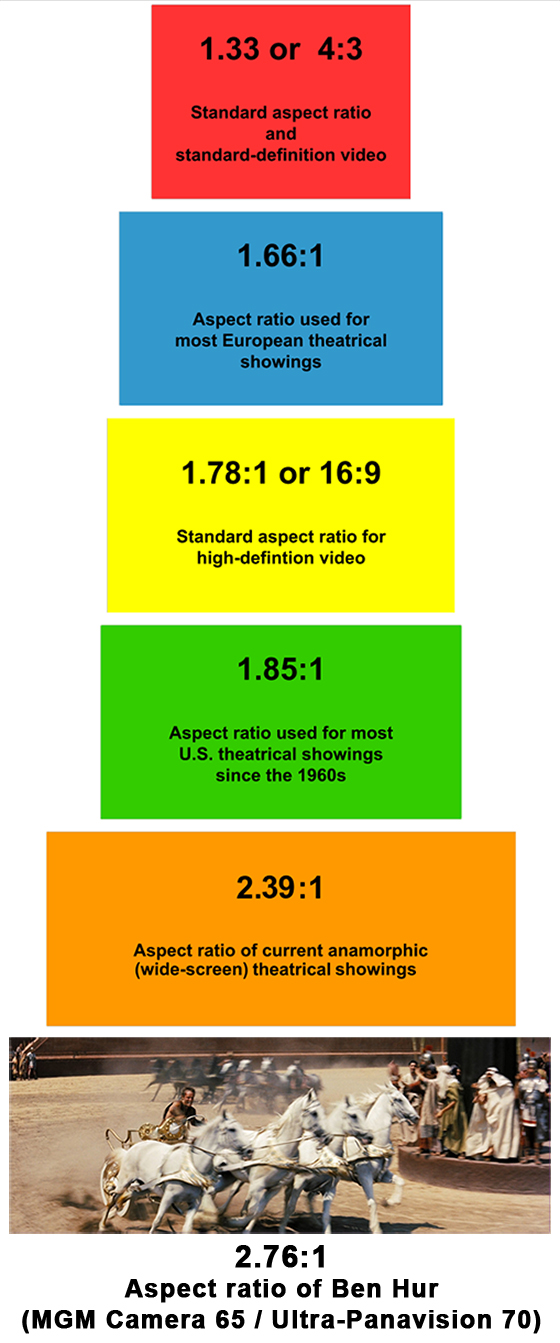

The widescreen visuals by cinematographer by Stephen H. Burum are not up to the iconic work of Gordon Willis on The Godfather or Vittorio Storaro’s work on Apocalypse Now, but they are often elegantly framed and look as good as they’ve ever done on this Blu-ray release.

However, there’s something about the film that lacks the magic ingredient to make it truly special and three years later Rob Reiner’s Stand By Me (1986) would capture a similar period with much more weight and charm.

It seems Coppola never fully recovered from the arduous production of Apocalypse Now and the personal hell of that period perhaps meant he wasn’t prepared to go to the creative extremes that he had previously.

That said, this Blu-ray is interesting as it features the special DVD cut which came out in 2005 after the director decided to reinsert scenes which were omitted for commercial reasons first time around.

Part of Coppola’s deal after the huge success of The Godfather was ownership (or part-ownership) of his work and one of the benefits is that his company Zoetrope keeps the negatives in decent condition.

The 1080p restoration presented in its proper aspect ratio of 2:35 is excellent and makes the period come alive in a way that earlier formats didn’t allow, with the colours and tones looking resplendent.

A new 5.1 DTS HD Master audio track is also solid, boosting the dialogue and early 1960’s soundtrack.

SPECIAL FEATURES

- Director’s cut Version with 22 minutes of new footage: Given that this has never been shown that much on UK TV in recent years, perhaps some viewers here won’t remember the original cut. If you listen to the cast commentary they sometime express surprise at a scene or musical cue that wasn’t in the original. Given that the film was inspired by fans writing a letter to Coppola and that distributor Warner Bros. persuaded him to make it shorter, it is appropriate that he should put back those missing scenes for this version.

- Introduction and New audio Commentary by Francis Ford Coppola: As with Coppola is an engaging presence on the commentary track describing his aims with the film and sharing production stories. Listen out for his paternal pride when his daughter Sofia makes a cameo.

- Audio commentary by Matt Dillon, C. Thomas Howell, Diane Lane, Rob Lowe, Ralph Macchio and Patrick Swayze: One of the nice things that Coppola does when he revisits a film for the DVD or Blu-ray versions is to do some ‘reunion’ interviews with cast members. In 2005 he assembled C. Thomas Howell, Diane Lane, Ralph Macchio and Patrick Swayze for dinner and afterwards they sat down to watch the film and their commentary was recorded. Matt Dillon and Rob Lowe’s commentary was dubbed in later, although the transitions are pretty seamless, and it is a little like a high school reunion with the good vibes coming across nicely.

- Staying Gold – A Look Back at The Outsiders: A nice retrospective documentary with interviews from cast and crew. Coppola’s use of the then new technology of video to record rehearsals makes for some interesting footage of the young cast.

- S.E. Hinton on Location in Tulsa: The author takes around the locations which inspired the novel and became places where they later filmed sequences for the movie.

- The Casting of The Outsiders: Producer Fred Roos became famous earlier in his career for casting Petulia (1968) and his eye for emerging actors came in especially handy with The Outsiders. It became famous as a showcase of actors who would go on to have significant careers.

- 7 cast members read extracts from the novel: Another nice touch as Lowe, Swayze, Howell, Dillon, Macchio, Garrett and Lane read extracts from the novel like it was a radio play (it was recorded in 2005).

- NBC’s News Today from 1983 The Outsiders: A news report from around the release of the film highlighting the story of the school children who wrote to Coppola requesting that it become a film.

- Started by School Petition: A short feature on the origins of the project.

- Six deleted or extended scenes

- Trailer from 1983

> Find out more about the original novel at Wikipedia