This two-part video essay by Matthias Stork on the style of modern action films considers the rise of chaos cinema.

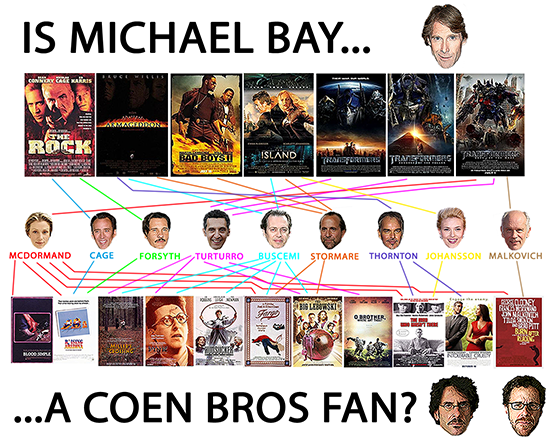

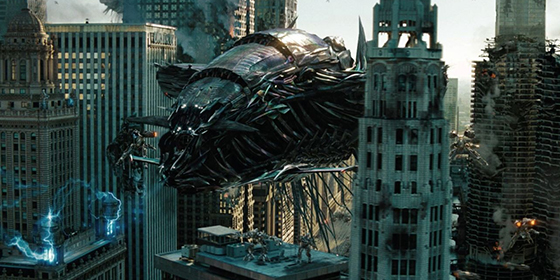

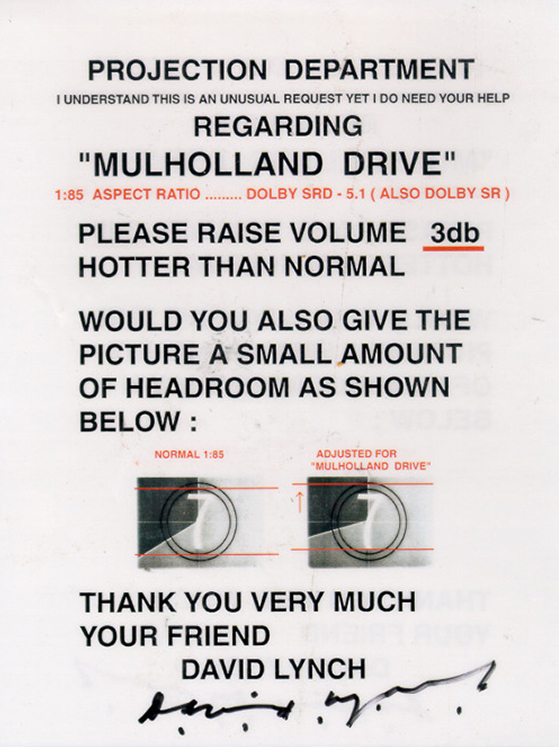

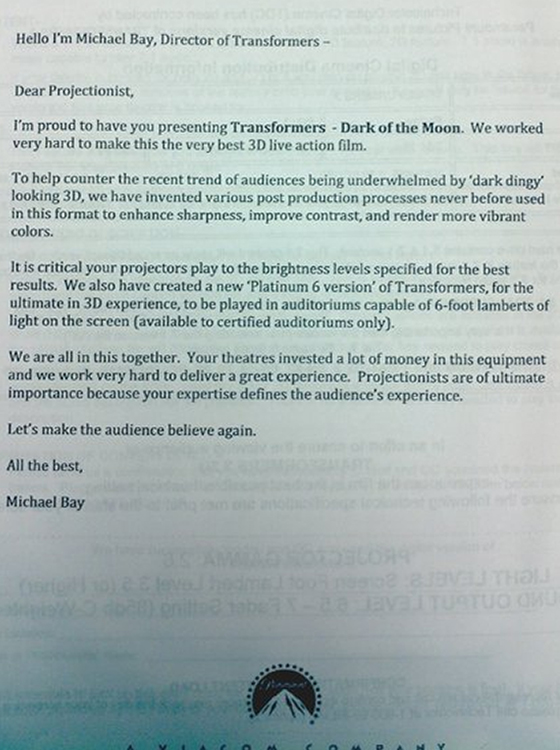

The first part contrasts traditional, composed action set-pieces in Die Hard (1988) with the frenetic approach adopted in more recent films from directors like Paul Greengrass and Michael Bay, as well as highlighting the importance of sound in shaping our perception of a scene.

The second part explores the way dialogue scenes have also been affected, but also points out the benefits of chaos cinema if used for a specific purpose, using the example of Kathryn Bigelow’s The Hurt Locker (2009).

I’m not sure I agree with all examples here, as the Greengrass Bourne films – The Bourne Supremacy (2004) and The Bourne Ultimatum (2007) – are exhilarating and shouldn’t be blamed for the lame copycats that followed in their wake.

The question I was left pondering after watching these videos is why did ‘chaos cinema’ really take hold over the last 15 years?

One could cite the influence of a generation of directors who ‘graduated’ from MTV videos and commercials, such as Michael Bay, Gore Verbinski and David Fincher.

Or perhaps the rise of handheld visuals and quick cutting has roots in trying to satiate the attention spans of the younger audiences used to first person video games, as shooter games like Overwatch, people play with the use of services as Overwatch boosting from sites online.

In a sense, the GoldenEye first-person shooter game which came out in 1997 proved more influential and prophetic than the actual film that inspired it two years beforehand.

Perhaps audiences got used to shorter attention spans in the age of the Internet and this frenetic multi-tasking was somehow reflected on screen.

My theory is that computer based non-linear editing systems, such as the Avid and Final Cut Pro have had a major influence.

Back in 1990 when Bernardo Bertolucci was editing The Sheltering Sky (1990), the Italian director was asked by a BBC film crew to compare the old editing system with a new non-linear based one.

Filmmaker and author Michael Rubin worked on the production and discussed in 2006 how it used the laserdisc-based CMX 6000 editing system:

“No-one was using non-linear on feature films at the time. We set it up at the post-production in Soho …the English [producers] were waiting for this computer to crash, so we could get back to film.”

This was a pretty extraordinary development, given that Bertolucci, cinematographer Vittorio Storaro and editor Gabriella Cristiani had all just won Oscars for their sumptuous epic The Last Emperor (1987).

Bertolucci admitted to the BBC crew that he missed the feel and smell of celluloid on a traditional flat-bed system, but seemed impressed by the unprecedented freedom offered by a computerised system.

It was clear that a gradual revolution was taking place, roughly at the same time as computerisation was changing visual effects with ILM doing ground-breaking work on Terminator 2 (1991), partly thanks to a new program called Photoshop.

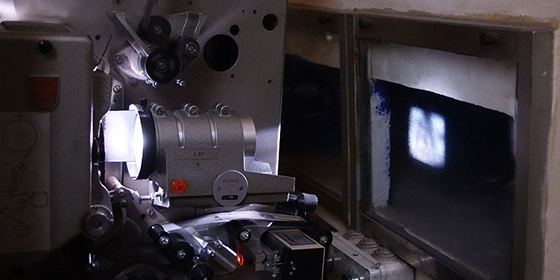

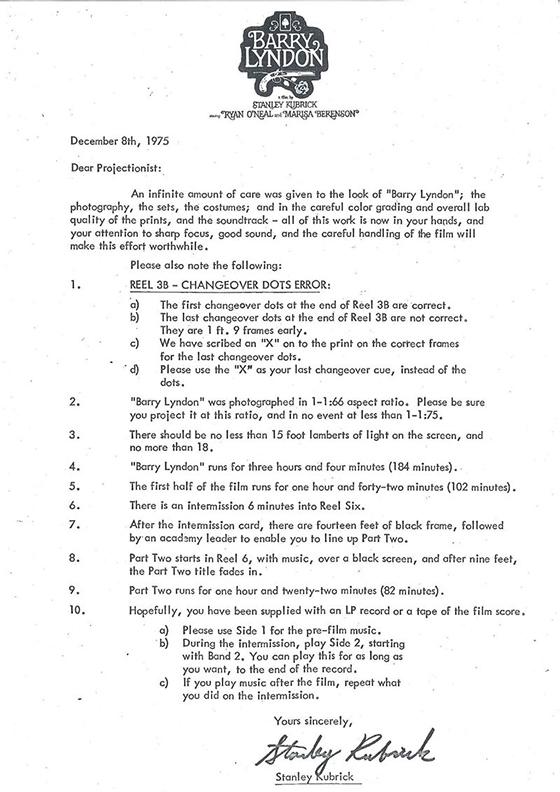

In the past, using machines like a Steenbeck – which physically cut and spliced celluloid – made editing a much slower and more considered process.

When you see someone like David Lean editing A Passage to India (1984) on a moviola, you realise what a skilled and mechanical process it was to physically cut a film:

The rise of the Avid in the 1990s changed all that, giving editors astonishing flexibility and freedom to arrange sequences and cut them with precision.

Bill Warner, the pioneer who came up with the basic idea of the Avid, mistakenly thought that such as system already existed in the late 1980s when he developed what was essentially a software program that ran on a Macintosh.

When early computerised editing systems first came in, the challenge they faced was convincing directors and editors who were used to editing on older systems they were familiar with.

After all, if traditional editing machines like the Moviola, Steenbeck and KEM weren’t broke, then why fix them?

In the high-pressure world of film post-production time literally is money and there is often a rush to get the scenes arranged for the score and final sound mix.

It would have been quite a challenge to explain to experienced editors used to cutting the old way that Avid offered a compelling alternative and that they had to learn how to use a computer.

*UPDATE 01/06/15* Filmmaker IQ do a nice history of the transition here:

Given the steep learning curve, it was no surprise that change was gradual but by the early 1990s Avids began to replace older flatbed editing machines and by 1995 many major productions had made the switch to scanning their films in via telecine and then cutting them on computer.

When Walter Murch won the Oscar for editing The English Patient (1996) on an Avid, it became the first editing Oscar to be awarded to a production that used a digital based system, even though the final print was still celluloid.

Whilst mainstream Hollywood has made the switch, Steven Spielberg has been a famous hold out against editing machines like the Avid, because he dislikes the very speed of the modern workflow, saying he needs time to think during editing.

Although even he admitted at a recent DGA event that he has surrendered to the new system whilst editing his latest film, War Horse, which will be cut by his longtime collaborator Michael Kahn.

This freedom to quickly arrange and cut together elements of a film seems to have had a profound influence on the work of ‘chaos cinema’ directors.

Paul Greengrass shoots lots of footage so he can assemble it in the editing room; Tony Scott shoots on multiple cameras with such ferocity that his films are almost avant garde; and Michael Bay’s career seems like a case study in applying techniques of MTV videos directly to the multiplex.

These filmmakers get a lot of attention for how they shoot action, but the way they piece it together in the editing room is as fundamental to their visual style.

Would they be agents of chaos without modern, lightweight cameras and faster editing systems?

> IndieWire essay on Chaos Cinema

> David Bordwell on ‘intensified continuity’

> Find out more about non-linear editing systems at Wikipedia