In the early 1970s director Alexander Mackendrick used the Watergate hearings to explore the basics of film grammar.

After establishing himself as a director with vintage Ealing comedies in the late 1940s, he returned to America where he made the classic Sweet Smell of Success (1957) with Burt Lancaster and Tony Curtis.

In 1969 he went into teaching at the California Institute of the Arts, where his students included future filmmakers such as Terence Davies, F. X. Feeney and James Mangold.

As the Watergate scandal heated up with saturation television coverage, Mackendrick noticed that the principles of narrative filmmaking could be applied to real-life television coverage.

For those not familair with Watergate, it began with a seemingly minor burglary at the Democratic campaign headquarters at the Watergate Hotel in 1972, and as Washington Post reporters probed the story, they gradually uncovered widespread criminal behaviour and evidence of a cover-up within the Nixon administration.

The Senate Watergate Committee began hearings in May 1973 and after several dramatic revelations, Nixon was forced to resign in August 1974.

Over the course of that year leading to his resignation, various people were called to testify to the committee, which were broadcast live on TV.

One exchange that caught Mackendrick’s attention was the between Senator Howard Baker and Sally Harmony, who secretary to G. Gordon Liddy, one of the key Nixon operatives later convicted of conspiracy, burglary and wiretapping.

You can watch the footage here:

Mackendrick was struck by the inherent drama of the conversation and the visual language of what unfolded on his television set.

He even wrote a detailed pamphlet which explored how the principles of a dramatic film apply to documentaries.

It makes for fascinating reading, but this particular quote stands out:

“It’s my guess that a movie director, given dailies of exactly the same footage, could hardly have done a better job of editing even if given time to analyse the material. The rapidly intercut closeups may be silent, but their subtext is obvious and eloquent. Seeing these live broadcasts from Washington, I remember being transfixed by what was essentially news reportage.”

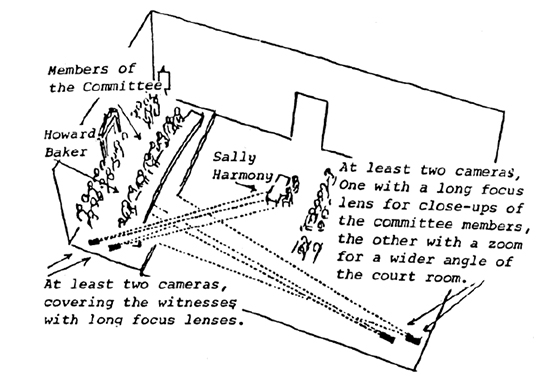

He even sketched out a diagram of where the cameras were in relation to the people:

The interesting thing is that you can apply Mackendrick’s analysis to any non-fiction footage, be it reality television, YouTube videos or serious current affairs.

The most seismic news event of the past decade was 9/11, a terrorist attack which many people at the time remarked was ‘like a movie’.

On NBC’s live coverage, a terrified witness on the phone says these very words at 04.21:

Presumably part of the terrorist plan was to use the Western media against itself, as they knew these images would be carried around the world.

The catch 22 for media is that they had to broadcast them as it was a major news story, but they also knew that the terror was being fed into millions of living rooms across the world.

Although the live coverage was edited in real-time, the way in which the images came together for audiences was like a dreadful disaster movie unfolding live on television. (For more on 9/11 and the movies click here)

On a very different note, Susan Boyle’s famous appearence on Britain’s Got Talent was massively popular because it was a classic underdog story compressed into 6 minutes.

Susan Boyle – Singer – Britains Got Talent 2009 by moovieblog

But notice several key points in the narrative:

- Simon Cowell’s doubtful look at 1.06

- Notice the cut to a sceptical audience member at 1.24 right after Boyle talks about her dream of being a professional singer

- Simon Cowell’s raised eyebrows at 1.59 which indicate the moment where the underdog has come good

- Amanda Holden’s eyes opening at 2.01 which accentuates that Boyle can really sing

This wasn’t quite live, but the basic narrative building blocks of what made it resonate were shaped in editing.

It currently has over 72 million views on YouTube (the reason I can’t embed from that particular site is a whole other story).

Mackendrick’s basic observations still resonate because they tap into the way in which human beings process the moving image.

Keep an eye out for any factual footage, be it on a serious news or the tackiest reality TV and notice how it is constructed.

You’ll probably find out more than you might initially think.

> Alexander Mackendrick at the IMDb

> More on Mackendrick and the Watergate footage at The Sticking Place