Martin Scorsese’s documentary about George Harrison is an absorbing and surprisingly spiritual examination of the late musician.

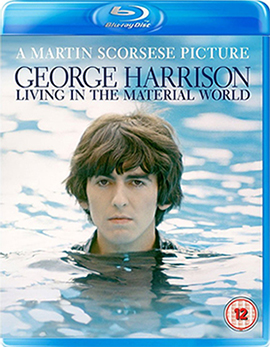

After screening at the Telluride film festival last month, this 208 minute film recently aired on HBO in the US and has just come out on Blu-ray and DVD in the UK before a screening on BBC Two later this year.

Part of the realities of modern movie distribution mean that this long-form work only got a brief screening at cinemas around the UK last week, before its arrival in shops on Monday.

But it marks another landmark musical documentary for Scorsese after No Direction Home (2005), his outstanding film about Bob Dylan, as it charts the cultural impact of the Beatles from the perspective of its most reflective member.

This not only gives the familiar subject a fresh feel, but it also goes into deep and moving areas as it charts how he dealt with the onslaught of fame and attention that came with being in the biggest band in the world.

Made with the full co-operation of Harrison’s family – his widow Olivia and son Dhani – it features interviews with them, bandmates Paul McCartney and Ringo Starr, plus numerous friends and acquaintances including Yoko Ono, George Martin, Eric Clapton, Astrid Kirchherr, Klaus Voormann, Eric Idle, Phil Spector (before his 2009 murder conviction) and Tom Petty.

Made with the full co-operation of Harrison’s family – his widow Olivia and son Dhani – it features interviews with them, bandmates Paul McCartney and Ringo Starr, plus numerous friends and acquaintances including Yoko Ono, George Martin, Eric Clapton, Astrid Kirchherr, Klaus Voormann, Eric Idle, Phil Spector (before his 2009 murder conviction) and Tom Petty.

Split into two parts the first deals with his childhood in Liverpool, the early days of The Beatles in Hamburg and their eventual rise to the dizzying heights of global fame, whilst the second explores how he dealt with that fame, becoming a solo artist, staging charity concerts, financing Monty Python films and his growing interest in Indian music and philosophy.

Scorsese has long had an interest in rock music but here he seems to have found a kindred spirit in Harrison, whose desire to transcend the surface trappings of fame provides the real fuel for this film.

Brilliantly assembled from a wealth of archive footage, including some vintage photography of the Fab Four and lots of material from the Harrison home movie collection, it creates a fascinating portrait of a musician who unwittingly became part of something huge.

For Beatles fans, it doesn’t attempt the scale of the 11-hour Anthology project from 1995 – still the definitive filmed history of the band – but gives us a different perspective outside of the Lennon-McCartney axis and provides us with unexpected pleasures as it charts his spiritual growth.

There is the persistent theme running throughout that Harrison was the dark horse of the group, a songwriter who gradually became the equal of his more illustrious band mates and on Abbey Road actually surpassed them by writing Something (described by Frank Sinatra as one of the greatest love songs of the 20th century) and Here Comes the Sun.

Scorsese also captures the dizzying cultural ascendency of The Beatles as they conquer the music world and become icons.

It touches on the dynamics within the band: George’s early friendship with Paul, which later led to tensions caught on film during the Let it Be sessions, the bewildering rush of fame and money and how this affected their lives.

One revealing bit of footage early on sees the band members sign the official contracts that dissolved the group in 1970 – Harrison is uttering an Indian mantra as he signs, which hints at his trepidation at the end of an era but also his growing interest in Eastern spirituality.

Throughout his time in the Beatles he had written songs where this was noticeable – Love to You, Within Without You and The Inner Light – but, after forging a close friendship with Ravi Shankar, he seemed to be the only one who fully embraced both the musical and spiritual dimensions of something the rest of the band just flirted with.

This may explain why he made a great solo album – All Things Must Pass – very soon after The Beatles broke up and could navigate the subsequent years with a degree of serenity and humour.

These times included: the Concert for Bangladesh (a benefit gig that foreshadowed Live Aid); a bizarre divorce from first wife Patti Boyd (his friend Eric Clapton essentially stole her with his ‘blessing’); the purchase of a large Victorian estate (Friar Park in Henley-on-Thames); film production (he created Handmade Films after financing Monty Python’s The Life of Brian) and his love of F1.

For film aficionados his patronage of The Life of Brian (1979) – which was hugely controversial amongst some observers – and films such as Time Bandits (1981), The Long Good Friday 1980), Mona Lisa (1986) and Withnail & I (1987) was really quite remarkable.

His reason for stumping up the $4m to fund Life of Brian – “because I wanted to see the film” – was both the most brilliant and eloquent reason ever given by a film financier and as Eric Idle points out was “the most expensive cinema ticket in history”.

Going in, I was expecting the film to tail off towards the end, as it deals with the last phase of his life, but it is to the films great credit that it manages to hold the attention right until the closing credits.

His second wife Olivia and son Dhani speak movingly about his home life and his struggles with cancer that were made worse by a home invasion and assault in 1999.

That nasty attack, which Dhani believes shortened his life, had chilling echoes of Lennon’s death at the hands of Mark Chapman in 1980 – an event which was extra painful for George, as he was deeply concerned with the manner in which the human spirit leaves the body.

A lot of family archive material was made available and editor David Tedeschi, who also worked on Scorsese’s Dylan documentary, has managed to arrange it with considerable skill and judicious use of music.

It also sounds great, thanks to the new 5.1 surround mix that was done by a team including George Martin’s son, Giles, who worked on the recent Love remixes.

There is always the danger of hagiography when it comes to films about famous figures, but this manages to paint a broad and interesting look at Harrison’s life without slipping into sentimentality.

Scorsese has long been interested in spirituality, whether it be the Catholicism of The Last Temptation of Christ (1988) or the Buddhism of Kundun (1997), and here he digs deep into Harrison’s spiritual awareness and how it kept him sane after the global goldfish bowl that was life during and after The Beatles.

Like Harrison himself, the film contains surprising depths and offers a refreshing glimpse into the world’s most famous band from the perspective of its most thoughtful member.

> Buy it on Blu-ray or DVD at Amazon UK

> IMDb entry

> More on George Harrison at Wikipedia

2 replies on “George Harrison: Living in the Material World”

George Harrison ‘Living in a Material World’ in review http://www.comicbookandmoviereviews.com/2011/11/george-harrison-living-in-material.html

One of the all time great songs. It always takes me “there” … to that sunny day at dawn. What beewrdils me, and something that we may never know, is how George Harrison didn’t become more of a musical and literary force after his Beetle days. He was the moving force arguably behind their masterpiece — Revolver. But I should be thankful for what he did give us!