Despite his (deserved) status as one of the most revered film critics around Roger Ebert does have something of a reputation of being too generous to films that don’t quite cut the mustard.

Interestingly, he has addressed this in an interesting blog post entitled “You give out too many stars”.

He writes:

That’s what some people tell me. Maybe I do.

I look myself up in Metacritic, which compiles statistics comparing critics, and I find: “On average, this critic grades 8.9 points higher than other critics (0-100 point scale).” Wow. What a pushover.

Part of my problem may be caused by conversion of the detested star rating system. I consider 2.5 stars to be thumbs down; they consider 62.5 to be favorable. But let’s not mince words: On average, I do grade higher than other critics.

Now why do I do that? And why, as some readers have observed, did I seem to grade lower in my first 10 or 15 years on the job?

I know the answer to that one. When I started, I considered 2.5 stars to be a perfectly acceptable rating for a film I rather liked in certain aspects.

Then I started doing the TV show, and ran into another wacky rating system, the binary thumbs. Up or down, which is it?

Gene Siskel boiled it down: “What’s the first thing people ask you? Should I see this movie? They don’t want a speech on the director’s career. Thumbs up–yes. Thumbs down–no.”

My gut feeling is that the star system for rating any artistic endeavour is flawed.

I know that a lot of people (amongst them many readers and editors) like it as it makes their choices easier, but my central problem is that it reduces everything to a simplistic maths equation.

Although in the past I have given marks out of ten and stars out of five to films when asked, I do so reluctantly.

My belief is that if someone can’t convince you of the merits of a particular film, book, play, album (or whatever) through the strength of their words alone, then they really shouldn’t be reviewing it in the first place.

There is also the added complication of whether to use marks out of four, five, ten or hundred. It seems to me that publications are pretty arbitrary on this, even though it has a massive effect on the final grade.

But perhaps the worst thing about the star system is that it is applying maths to art. I don’t believe anyone (whether they be Andy Warhol, Michael Bay, Werner Herzog or Martin Scorcese) sets out to make a film to fit into a scientific formula – so why do we feel we have to grade them like one?

But back to Roger, he lists the reasons why he grades higher than the Metacritic average:

But back to Roger, he lists the reasons why he grades higher than the Metacritic average:

But forget ratings systems altogether. What inclines me to tilt in a more favorable direction?

I submit the following possibilities:

1. I like movies too much. I walk into the theater not in an adversarial attitude, but with hope and optimism (except for some movies, of course). I know that to get a movie made is a small miracle, that the reputations, careers and finances of the participants are on the line, and that hardly anybody sets out to make a bad movie…

On this I have a lot of sympathy with Roger, as I too always go to a film hoping it will be good. Why would you be doing a job like this if you didn’t?

That said, I’m often surprised at how often this isn’t the case – at times some critics and ‘media’ audiences I’ve been amongst almost seem to relish trashing a bad or average film more than actually celebrating a good or excellent one.

in my line of work I am often stunned at the amount of people you meet who appear to actually dislike the act of going to the cinema and watching a film (even if this is their job!).

In the UK, where TV and Theatre appears to have a higher social and cultural standing than Film, there is still – in some influential quarters – a certain snobbishness about the medium.

This usually leads to a kind of pointless grumbling about ‘Hollywood trash’, even though Britain, Europe and the rest of the world have also contributed to the collective cesspool of bad films.

But anyway, Roger’s second reason is:

2. Directors. There are some who make films I simply find myself vibrating with. I will have difficulty in not admiring a work by Bergman, Altman, Fellini, Herzog, Morris, Scorsese, Cox, Leigh, Ozu, Hitchcock, Kurosawa, Keaton…and to borrow an observation from my previous entry, I haven’t even reached directors under 60.

This is undeniable. Although I’m not a fully paid up subscriber to the Auteur Theory, there is no doubt that this is a director’s medium.

Even if you don’t fully engage with a particular film, the stamp of the director -and how it compares to his other work – is certainly a factor is passing judgement on it.

His third rule:

3. I feel strongly about actors I admire, watching their ups and downs and struggles to work in a system that often sees them only as meat. Example. I opened my review of “The Women” this way: “What a pleasure this movie is, showcasing actresses I’ve admired for a long time, all at the top of their form. Yes, they’re older now, as are we all, but they look great, and know what they’re doing.”

Yes, I really believe that. I interviewed Candice Bergen for the first time in 1971. God, she was wonderful. I mean as a person. She was one of the most beautiful women in the world, and she married Louis Malle, and was happy. Louis Malle was beautiful too, if you know what I mean, and a great filmmaker. She fell in love with both her head and her heart. I felt a particular pleasure in seeing her and that whole cast together.

Hmmm. Whilst I appreciate that audience members (be they experienced critics or young kids going to the cinema for the first time) form attachments to certain actors, one of the basic tenets of decent criticism is that you should be honest about their bad work as much as they best.

I am a huge admirer of Al Pacino, a screen icon who has performed brilliantly in the The Godfather, Serpico, Dog Day Afternoon and The Insider.

But that doesn’t mean that I should cut any slack to a film like 88 Mins, which is one of his worst performances and, generally speaking, a laughable piece of crap.

To be fair though, that is primarily a problem with the writing and direction, for no actor can create a decent performance with a weak script.

Rule 4:

4. Once the scent of blood is in the water, the sharks arrive. I like to write as if I’m on an empty sea. I don’t much care what others think. “The Women” scored an astonishingly low 28 score at Metacritic. “Sex and the City” scored 53. How could “The Women” be worse than SATC? See them both and tell me. I am never concerned about finding myself in the minority.

This is a fair enough – people should write their own feeling and not subscribe to critical ‘group-think’. But equally we shouldn’t go all contrarian and swim against the prevailing tide just to stand out.

Rule 5:

5. I have sympathy for genres, film noir in particular. I am almost capable of liking a movie simply for its b&w noir photography. I like science fiction. Ed Harris has a new Western coming out named “Appaloosa.” I’ll like it more than the Metacritic average. You wait and see.

Although I understand Roger’s passion here – I think we all have genres we prefer – I really do think the quality of a film trumps whatever genre it is in.

For example romantic comedy has increasingly – and sadly – become a genre that signifies a badly written pile of rubbish aggressively marketed to a female audience.

But when judging it, we shouldn’t excuse because of it’s genre, rather we should explain why it is good, bad or average. In short, genres shouldn’t be an excuse.

Rule 6:

6. In connection with my affinity for genres, in the early days of my career I said I rated a movie according to its “generic expectations,” whatever that meant. It might translate like this: “The star ratings are relative, not absolute. If a director is clearly trying to make a particular kind of movie, and his audiences are looking for a particular kind of movie, part of my job is judging how close he came to achieving his purpose.”

Of course that doesn’t necessarily mean I’d give four stars to the best possible chainsaw movie. In my mind, four stars and, for that matter, one star, are absolute, not relative. They move outside “generic expectations” and triumph or fail on their own.

As for rule 5, I think Roger is on sticky ground here. I understand that certain audience members have certain genre expectations (e.g. horror fans want to be scared or grossed out, comedy fans go to laugh) but I think that the individual voice of a critic is important.

Pauline Kael seemingly loved almost anything Brian De Palma directed whilst deriding Stanley Kubrick and Woody Allen, but I think people read her New Yorker reviews because of that snobbish, whacky passion.

In a similar vein I think readers love Roger for his generous attitude, wide ranging knowledge and deep passion for movies.

Trying to adjust your own critical personality along genre lines could be selling yourself a bit short.

Rule 7:

7. I have quoted countless times a sentence by the critic Robert Warshow (1917-1955), who wrote: “A man goes to the movies. The critic must be honest enough to admit that he is that man.”

If my admiration for a movie is inspired by populism, politics, personal experience, generic conventions or even lust, I must say so. I cannot walk out of a movie that engaged me and deny that it did. I must certainly never lower it from three to 2.5 so I can look better on the Metacritic scale.

This is a solid point. Any viewer of a movie with an opinion brings to it their own unique life experiences, so to artificially adjust or deny them is silly.

That said, the Metacritic average system points brings up an interesting issue. It is very rare that I disagree with films that get high (above 70) or low (below 40) scores.

Does this mean that critics tend to think alike? What would happen if we ran the Metacritic scores against the box office numbers? Or for that matter the IMDb 250?

How big a disparity would there be between the so-called experts and the paying audience?

Your thoughts are welcome.

> Roger’s original blog post at RogerEbert.com

> Metacritic and the individual scores for Roger

> Jeffrey Wells with his thoughts at Hollywood Elsewhere

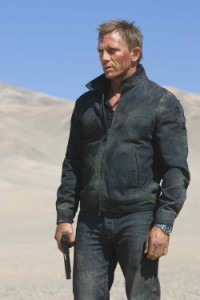

After an opening sequence in Italy, the trail leads him to Haiti – the back to Italy – and eventually to Bolivia where he encounters the mysterious Dominic Greene (Mathieu Amalric), a key player in the Quantum organisation that blackmailed Vesper and is now involved in destabilising regimes in Central America.

After an opening sequence in Italy, the trail leads him to Haiti – the back to Italy – and eventually to Bolivia where he encounters the mysterious Dominic Greene (Mathieu Amalric), a key player in the Quantum organisation that blackmailed Vesper and is now involved in destabilising regimes in Central America. Whilst Almaric is a great actor (he was phenomenal in The Diving Bell and the Butterfly last year) his villain here feels a little underwritten – perhaps because he isn’t the true number 1 of the organisation?

Whilst Almaric is a great actor (he was phenomenal in The Diving Bell and the Butterfly last year) his villain here feels a little underwritten – perhaps because he isn’t the true number 1 of the organisation?