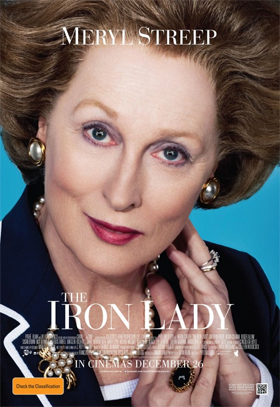

Despite a masterful central performance this political biopic ends up caught between hagiography and melodrama.

Adopting a flashback structure, it sees the ageing politician (Meryl Streep) looking back on key episodes of her life: her humble origins in Leicestershire; her early years as an MP; her rise to power and the key episodes from her lengthy tenure as prime minister from 1979-1990.

The highlight here is a typically brilliant performance from Streep, who uses the full arsenal of her acting repertoire to create a striking portrait of Britain’s first female leader.

Her physical and vocal work is uncanny, which is no mean feat considering the years covered by the film, which sees newcomer Alexandra Roach play the younger version with considerable poise and presence.

These early segments of the film depict the cosy, sexist world of both the Tory party and Britain during the late 1950s (she became an MP in 1959) which almost certainly fed into her later assault on various British institutions.

Director Phyllida Lloyd has an extensive background in musical theatre and it shows here in the heightened zig-zag sweep of the narrative, which is a curious mixture of feminist biopic and political opera (minus the music).

The central device is both a blessing and a curse – it captures the irony of a frail Thatcher needing help (when her whole philosophy was built on a ruthless self-reliance) but the clunky use of her late husband Denis (Jim Broadbent) gets ever more comic as the story progresses.

At times it feels like that most curious of things: an interesting mess that is filled with fascinating contradictions.

Lloyd and her DP Elliot Davis frequently use distracting compositions and in some sequences Justine Wright’s editing is frenzied to the point of incoherence.

Lloyd and her DP Elliot Davis frequently use distracting compositions and in some sequences Justine Wright’s editing is frenzied to the point of incoherence.

Yet there is also much technical work here to admire in bringing Thatcher to life: Marese Langan‘s hair and makeup design is the real standout, with Consolata Boyle‘s costumes not far behind.

In fact they are almost as impressive as the job Gordon Reece (played in the film by Roger Allam) did for Thatcher.

This duality feels weirdly appropriate for a film about a prime minister who was so hated that she ended up getting elected three times.

It says a lot about the conflicted mental state of the United Kingdom that Thatcher is so loathed and revered, which is appropriate for a nation still thoroughly divided about its social and cultural identity.

(If you are in any doubt just ask yourself about the differences between the United Kingdom, Great Britain, England, Scotland, Wales and that’s before you even get to the long and complicated history with Ireland)

This film tries to have it both ways, by depicting the downward vulnerability of her old age whilst contrasting it with the ambitious vigour of her political career.

Whilst this could be seen as avoiding the thornier issues of her reign, the director, screenwriter and star are all women in an industry dominated by men – presumably they saw this as something of a feminist fable of a female leader taking on male institutions.

That Thatcher routinely preferred the company of men and barely promoted women seems only to have piqued their interest in exploring the personal motivations lay behind her political ideology.

It is surprising but appropriate that the most effective relationship in the film is between Margaret and her daughter Carol (a brilliant Olivia Colman who is almost unrecognisable) in contrast to her absent son Mark, whom she clearly favoured.

There are traces of sneaky subversion in Abi Morgan’s screenplay, which appear to draw from Carol Thatcher’s 2008 memoir, which offer some intriguing glimpses into the private person behind the political persona.

For a leader who had so little time for the poor and dispossessed during her time in office there is something dramatically effective in seeing her suffer the uncertainties of old age.

Tory supporters hoping to enjoy scenes of Thatcher at the Commons dispatch box will be given pause by the scenes between mother and daughter – no wonder current PM David Cameron sounded genuinely uneasy when asked about the film.

It will be interesting to see how audiences react in Britain as this is traditionally the kind of heritage filmmaking that conservative broadsheet newspapers lap up, whilst their liberal counterparts have commissioned endless think pieces on it too.

But when audiences get to see it, they may be surprised at what unfolds in front of them, which speaks to both the uneven qualities of the film and Thatcher’s legacy as leader.

She was the heartless destroyer of trade unions and the slightly saucy headmistress who bewitched a generation of voters to either buy their own council houses or shares in privatised industries.

There was also the lower middle class voting block – from the kind of towns where she herself came – who kept re-electing her.

Tellingly it took the public schoolboys like Geoffrey Howe (Anthony Head) and Michael Heseltine (Richard E. Grant) in her own party to bring her down.

One area the film fails to illuminate is her relationship with key media organisations: notably Rupert Murdoch (with whom she formed a lasting and mutually beneficial alliance) and the BBC (an organisation with who she has a complex and fascinating relationship) were key to her electoral success.

The late Christopher Hitchens once lovingly spoke of an encounter in the late 1970s where Thatcher smacked him on the bottom and called him a “naughty boy” with a twinkle in her eye.

Although sadly this episode isn’t in the film, there is a moment when the elderly Thatcher is asked about the current PM and describes him as a “smoothie”.

This is not only funny but also highlights the public school mind set of the British ruling elites and their unlikely infatuation with a woman who they’d previously dismissed as a grocer’s daughter.

Meryl Streep is perfect casting, as she is to modern Hollywood as Thatcher was to Parliament in the 1980s – although politically a liberal she has defied industry wisdom to maintain a healthy career as a female star.

Furthermore, Streep’s astonishing ability to do accents serves her well and her outsider status as an American in a very British cast also dovetails with the former PM’s outsider status.

Warren Beatty once said that her political soul mate Ronald Regan once told him:

‘I don’t know how anybody can serve in public office without being an actor.’

The Iron Lady reflects this idea of politician as performer – a great performance which nevertheless masks key deficiencies in other vital areas.

Given the recent implosion of the free market principles Reagan and Thatcher championed, the film functions as a curious epitaph for an era which there seems to be a strange nostalgia for.

> The Iron Lady at IMDb

> Find out more about Margaret Thatcher at Wikipedia

> Reviews of The Iron Lady at Metacritic

> Guardian data blog on how Britain changed under Thatcher