As in previous years this list of the best films of the year is presented in alphabetical order. (2007 titles which got a UK release during 2008 can be found in last year’s updated list).

THE BEST FILMS OF 2008

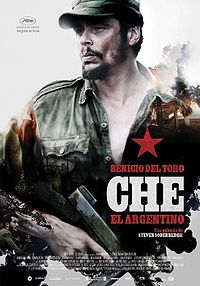

Che (Dir. Steven Soderbergh)

Che (Dir. Steven Soderbergh)

This long gestating biopic of Che Guevara from director Steven Soderbergh got a mixed reaction after it premiered at Cannes in May.

Some were put off by the four hour running time and the whole question of whether or not it was actually two films. It would probably be most accurate to describe it as two films merged together as one: The Argentine deals with the Cuban revolution in 1959 whilst Guerrilla explores his final years in Bolivia.

In the UK they will be released as Che: Part One and Che: Part Two, with some special double-bill screenings at certain cinemas. However you see it though, be sure to experience it on a big screen, as this an audacious and thrilling piece of cinema.

In the first part we see the Cuban Revolution inter-cut with Guevara’s 1964 trip to the United Nation and refreshingly Soderbergh eschews the narrative cliches of many historical biopics. Instead of ponderous meditations on his motives or background we are plunged into the raw action of the revolutionary’s life.

Some viewers may find this off putting but as the film progresses the production design, costume, acting and cinematography get ever more hypnotic, drawing us into this world.

Soderbergh has always been a gifted technical filmmaker interested in pushing the boundaries of mainstream cinema and here he has crafted one of his most interesting and accomplished films with the help of a revolutionary digital camera (appropriately called the RED One) that has allowed him to make an epic using guerrilla film-making techniques.

The spiritual core of the film is an outstanding performance from Benicio del Toro, who captures the physical and vocal mannerisms of Che so well that he manages to make you forget about the face that spawned so many t-shirts and posters.

[Che Part One is released in the UK on January 1st and Part Two on February 20th]

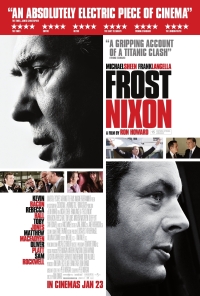

Frost/Nixon (Dir. Ron Howard)

Frost/Nixon (Dir. Ron Howard)

When I first saw Peter Morgan’s stage play about David Frost’s famous interviews with Richard Nixon in 1977, I remember wondering what a film adaptation might look like.

Although the hiring of Ron Howard to direct might have raised some eyebrows, to his credit he not only kept the two lead actors from the production (Michael Sheen as Frost and Frank Langella as Nixon) but also managed preserve the essential drama at the heart of the story and keep as faithful to it as possible.

For those of you unfamiliar with the background, Peter Morgan (who has become an expert in dramatising modern history scripting The Queen and The Last King of Scotland) created a play which explored the tensions behind Frost pursuing and then conducting Nixon’s first TV interviews since resigning in disgrace over the Watergate scandal.

What makes it so absorbing is the clash of two very different characters who for different reasons had a lot at stake: Frost was desperate to re-establish himself in America, whilst Nixon was keen to rebuild his shattered political reputation.

Technically, both lead performances are superb and after two years on stage together the chemistry between Sheen and Langella is magnetic.

The supporting cast is very solid with Rebecca Hall, Toby Jones, Matthew Macfadyen, Kevin Bacon, Oliver Platt and Sam Rockwell all making fine contributions in key roles.

Perhaps the most striking aspect of the film is how it manages to be both a fascinating slice of history garnished with some fine period design yet also finds a way of commenting on the current concerns about US politics.

It also poses a fascinating question: will President Bush ever come out with the same anguished mea culpa that Nixon delivered in these interviews?

[Frost/Nixon is released in the UK on January 25th]

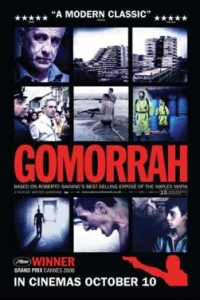

Gomorrah (Dir. Matteo Garrone)

Gomorrah (Dir. Matteo Garrone)

One of the darkest and most disturbing films of the year was this searing examination of crime in modern Italy. It didn’t just upend many of the traditional tropes of the Mafia in pop culture – it exploded them.

The narrrative was based on true life stories from Roberto Saviano‘s bestselling book about the Comorrah, a criminal organisation centred around southern Italy (especially Naples and Caserta).

There is a 13-year-old boy (Salvatore Abruzzese) who falls in with a criminal gang; a messenger (Gianfelice Imparato) who pays the families of prisoners; a young graduate (Carmine Paternoster) who gets involved in toxic waste management; a tailor (Salvatore Cantalupo) who wants to break free of local suppliers and two wannabe gangsters (Marco Macor and Ciro Petrone) who find a stash of weapons and want to act like Scarface.

Director Matteo Garrone cast the film impeccably and the ensemble acting was terrific but he also created a hellishly believable modern landscape far removed from that of mob movies like The Godfather, Goodfellas or The Sopranos.

This was a world riddled with poverty, tension and despair where crime infects everyone like a rampant virus. It paints a devastating picture not only of regions in modern Italy, but the tentacles of the Comorrah spread out to the wider world.

The film scooped the Grand Prix at the Cannes Film Festival, where it deservedly screened to critical acclaim.

Although at times it was an uncomfortable and brutal film to watch, it remains one of the most powerful and haunting crime films of the last decade.

* Listen to our interview with Matteo Garrone about Gomorrah *

[Gomorrah is available on DVD on February 9th)

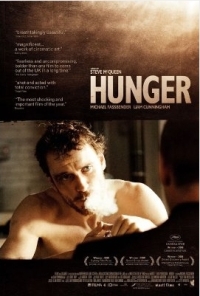

Hunger (Dir. Steve McQueen)

Hunger (Dir. Steve McQueen)

Every year there are a handful of films that know will end up in your ‘best of the year’ list as the credits roll and this stunning drama about the 1981 IRA hunger strike was just such a film.

A stark and harrowing look at one of the key episodes of The Troubles was about a group of IRA prisoners in the Maze led by Bobby Sands (a mesmerising performance from Michael Fassbender) went on a protracted hunger strike.

Their aim was to apply pressure against the British government, so that they could be classed as political prisoners and it marked a significant escalation in the conflict.

What the film managed to capture so well was the bitter brutality of life inside the prison – a world in which inmates refused to wear clothes, smeared excrement over their walls and were savagely beaten.

But at the same time this was no apologist for the IRA and perhaps the most shocking scene in the film explored the constant danger the prison guards lived under, where reprisals could lurk anywhere and at any time.

This is not a film that ‘takes sides’, but rather it explores the full human horror of The Troubles through the lens of the hunger strike – the physical brutality and sheer squalor point to the entrenched hatreds that ensnared all of those caught up in it. Echoes of Abu Ghraib and Guantanamo Bay are never far away.

The sounds and visuals were breathtaking with McQueen and cinematographer Sean Bobbitt showing a remarkable attention to detail whether it was a snowflake landing on the bloodied fist of a guard or urine gradually seeping out from beneath the cell doors before being gradually swept back in.

One lengthy sequence involving Fassbender and Liam Cunningham (who played Sands’ priest) was perhaps one of the most riveting and daring pieces of cinema I’ve seen in years.

This was an astonishing directorial debut for Steve McQueen, who has been best known until now as an acclaimed visual artist, but this holds the promise of a hugely successful career in feature films.

* Listen to our interview with Liam Cunningham about Hunger *

[Hunger is out on DVD on February 23rd]

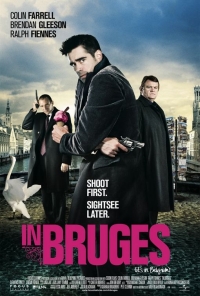

In Bruges (Dir. Martin McDonagh)

In Bruges (Dir. Martin McDonagh)

Perhaps the funniest film of the year was the directorial debut of the playwright Martin McDonagh, a brilliantly executed tale of two Irish hit men (Colin Farrell and Brendan Gleeson) who have been sent to lie low in the Belgian city of Bruges.

Not only does it contain several memorable sequences, but it contained the sort of ballsy, politically incorrect humour absent from a lot of mainstream comedy movies.

It also features some excellent performances, most notably from the two leads. Gleeson is his usual dependable self whilst Farrell shows what a good actor he can be when released from the constraints of big budget Hollywood productions.

Ralph Fiennes also made a startling impression in a menacing supporting role that owes more to his turn in Schindler’s List than some of his more recent performances.

If you are familiar with the sensibility of McDonagh’s plays, such as The Lieutenant of Inishmore, you will find much to feast on here – it feels like Harold Pinter’s The Dumb Waiter remade by Quentin Tarantino.

Despite a warm critical reaction, it didn’t really get the attention it deserved, which may have been down to bad marketing (the US one sheet poster was horrible and the UK one not much better) or the fact that the title confused people.

One sequence in a hotel room involving drugs, a hooker and a dwarf was one of the funniest things I’ve seen all year and is worth the price of admission.

[In Bruges is out now on DVD]

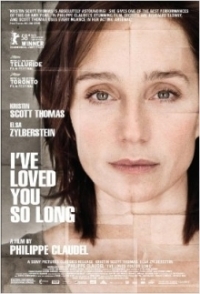

I’ve Loved You So Long (Dir. Philippe Claudel)

I’ve Loved You So Long (Dir. Philippe Claudel)

An intelligent and beautifully crafted portrayal of family love which revolved around two sisters named Juliette (Kristin Scott Thomas) and Lea (Elsa Zylberstein), who reconnected with one another after a prolonged absence.

To say too much about the plot would spoil the cleverly constructed narrative which gradually reveals their past and the reasons as to why they have been separated for so long.

Writer and director Philippe Claudel was better known as a novelist in his native France and this also shares many of the pleasures of well written fiction: nuanced characters, slow burning emotions and a real sense of the complexities of human relationships.

This is a film in which a lot of characters spend a lot of time in rooms talking about themselves, but at the same time manages to burrow deeply into the tangled emotions of it’s protagonist.

Much of the power comes from two marvellous central performances and Scott Thomas proved what a captivating screen presence in what is arguably the performance of her career so far.

Her work on stage – notably in Chekhov productions like Three Sisters and The Seagull – demonstrated that she had much more range and ability than some of her screen performances suggested, so it was gratifying to see her grapple with such a juicy part and take it to another level.

Credit must also go to Claudel for the way in which he has captured the small but subtle details that gradually reveal her character: the silence as she sits alone in a cafe, the wetness of her hair or even the way she smokes a cigarette.

Since screening at the Telluride and Toronto film festivals a few weeks ago, this film has had a good deal of awards buzz and deserves recognition for the sheer excellence of the writing and acting.

[I’ve Loved You So Long is released on DVD on February 9th]

Man on Wire (Dir. James Marsh)

Man on Wire (Dir. James Marsh)

British director James Marsh crafted a superb documentary about Frenchman Philippe Petit, who on August 7th 1974 gave an incredible high-wire performance by walking between between the Twin Towers of New York’s World Trade Center eight times in one hour.

The act itself almost defies belief but what the film does brilliantly is capture the tension, beauty and brilliance of Petit’s highly illegal operation.

Born out of a dream and an idea, Petit and his team of accomplices spent eight months planning the execution of their ‘coup’ down to the most intricate detail.

Like a team of bank robbers planning their most ambitious heist, the tasks they faced seemed virtually impossible: they would have to bypass the WTC’s security; smuggle the wire and rigging equipment into the towers; suspend the wire between the towers; secure the wire at the correct tension to withstand the winds and the swaying of the buildings; to rig it secretly by night – all without being caught.

The film is also an emotional experience – although it never mentions or shows footage from the 9/11 attacks, the Twin Towers are a haunting presence in the stock photos and footage from the time.

But the ultimate message of the film is a positive one as it reminds us that the joy and magic Petit created on the Twin Towers is still there, even though the actual building is not.

* Listen to our interview with Philippe Petit about Man on Wire *

[Man on Wire is out now on DVD]

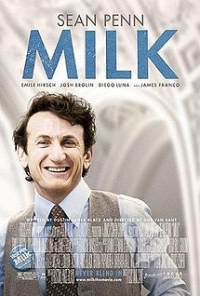

Milk (Dir. Gus Van Sant)

Milk (Dir. Gus Van Sant)

Sean Penn is often regarded as one of the finest actors of his generation and his portrayal of Harvey Milk in this biopic was one of his very best.

Milk was a gay rights activist who in the 1970s became the first openly gay man to be elected to public office in California as a member of the San Francisco Board of Supervisors.

The film opens with opens with archive footage of police raiding gay bars during the 1950s and 1960s, followed by the announcement in November, 1978 that Milk and Mayor George Moscone have been assassinated.

What follows is an inspiring and moving tale of political courage and hope with many fine performances across the board from Emile Hirsch, James Franco and Josh Brolin.

Directed by Gus Van Sant from a script by Dustin Lance Black, it skilfully juxtaposed the drama of Milk’s political battles against the inner conflicts of his private life.

It was also a nice change to see Penn play a warm and inspirational protagonist, an added dimension to the film which gave it an extra lift.

Watching the film unfold just a couple of weeks after the election of Barack Obama it was hard not to see the parallels: both were political outsiders who thrived on changing the status quo through a combination of hope and grass roots activism.

Sadly, Milk’s legacy was not enough to prevent the passing of Prop 8 – a California ballot proposition that changed the laws of the state to ban same sex marriage.

But this film will almost certainly become a lasting testament to his political and moral courage.

[Milk is out at UK cinemas on Friday 23rd January]

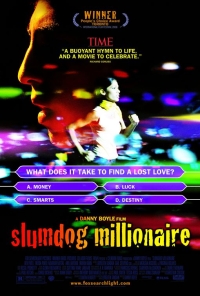

Slumdog Millionaire (Dir. Danny Boyle)

Slumdog Millionaire (Dir. Danny Boyle)

In the spring of 2007 director Danny Boyle told me that his next film would be set in Mumbai and was the story of a young man on the Indian version of Who Wants to Be a Millionaire.

But it was only afterwards that I started to wonder. Would the film be made in English? Would it be a Bollywood film? Comedy? Drama?

It is a testament to the final film that Slumdog Millionaire is so many different things – a vibrant and rich journey through modern India through the lens of a Dickensian tale of love and redemption.

Adapted by Simon Beaufoy from the novel Q and A by Vikas Swarup, it deservedly received a lot of buzz and acclaim at the Telluride and Toronto film festivals.

What’s interesting is that the narrative plays a little like The Usual Suspects, as we learn how the central character Jamal (Dev Patel) came to be on the game show.

It then flashes back to periods of his life growing up as a kid from the slums (or ’slumdog’ as some less than charitable characters in the film put it) and his desire to find the true love of his life (Frieda Pinto).

Boyle and his cinematographer Anthony Dod Mantle don’t shy away from the poverty of the slums in the film but also capture the live wire energy of Mumbai with some inventive use of digital cameras and a cracking soundtrack.

Whilst some audiences might be a bit taken aback by some of the darker sequences, they are necesssary counterweights for others aspects of the story to really work.

A huge amount of credit must go to Beaufoy who has constructed a jigsaw puzzle narrative that somehow manages to hold everything together in a way that is exciting, clever and moving.

Another clever touch is the realistic portrayal of the Who Wants To Be A Millionaire show, complete with the right music and graphics which are expertly woven into the film and play a key part in how the story unfolds.

The cheesy tension of the TV show somehow has a new life here, with added meaning on the tense pauses and multiple choice questions.

It is currently regarded as the front runner for Best Picture at the Oscars and deservedly so as it mixes serious social commentary with a classical tale of lost love into something truly special.

[Slumdog Millionaire is out at UK cinemas on Friday 9th January]

Synecdoche, New York (Dir. Charlie Kaufman)

Synecdoche, New York (Dir. Charlie Kaufman)

In the last decade Charlie Kaufman has become one of those rare screenwriters whose work has even overshadowed the directors he has worked with.

This is quite a feat given that he has collaborated with Spike Jonze (on Being John Malkovich and Adaptation) and Michel Gondry (Human Nature and Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind).

However, it is fair to say that all those films bear certain recognisable tropes: ingenious narratives, surreal images and a tragi-comic view of human affairs.

It would have also been a reasonable assumption to think his directorial debut would be similar, but Synecdoche, New York (pronounced “Syn-ECK-duh-kee”) does not just bear token similarities to his previous scripts.

In fact it is so Kaufman-esque that it takes his ideas to another level of strangeness, which is quite something if you bear in mind what has come before.

The story centres around a theatre director named Caden Cotard (Philip Seymour Hoffman) who starts to re-evaluate life after his health and marriage start to break down.

He receives a grant to do something artistically adventurous and decides to stage an enormously ambitious production inside a giant warehouse.

What follows is a strange and often baffling movie, complete with the kind of motifs that are peppered throughout Kaufman’s scripts: someone lives in a house oblivious to the fact that it is permanently on fire; a theatrical venue the size of several aircraft hangars is casually described as a place where Shakespeare is performed; and visitors to an art gallery view microscopic paintings with special goggles.

But despite the oddities and the Chinese-box narrative, this is a film overflowing with invention and ideas.

It explores the big issues of life and death but also examines the nature of art and performance – a lot of the film, once it goes inside the warehouse, is a mind-boggling meditation on our lives as a performance.

Imagine The Truman Show rewritten by Samuel Beckett and directed by Luis Buñuel and you’ll get some idea of what Kaufman is aiming for here.

I found a lot of the humour very funny, but the comic sensibility behind the jokes is dry and something of an acquired taste.

Much of the film hinges on Seymour Hoffman’s outstanding central performance in which he conveys the vulnerability and determination of a man obsessed with doing something worthwhile before he dies.

The makeup for the characters supervised by Mike Marino is also first rate, creating a believable ageing process whilst the sets are also excellent, even if some of the CGI isn’t always 100% convincing.

The supporting cast was also impressive: Catherine Keener, Michelle Williams, Samantha Morton, Emily Watson, Hope Davis, Tom Noonan and Dianne Weist all contribute fine performances and fit nicely into the overall tone of the piece.

Although the world Kaufman creates will alienate some viewers, it slowly becomes a haunting meditation on how humans age and die.

As the film moves towards resolution it becomes surprisingly moving with some of the deeper themes slowly, but powerfully, rising to the surface.

This means that although it will have it’s admirers (of which I certainly include myself) it is likely to prove too esoteric for mass consumption as it has a downbeat tone despite the comic touches.

Having seen it only once, this is a film I instantly wanted to revisit, so dense are the layers and concepts contained within it.

On first viewing it became a bit too rich at times for it’s own good but on reflection I don’t think I’ve seen a more ambitious or challenging film this year.

[Synechdoche, New York is out at UK cinemas on Friday 15th May]

The Class (Dir. Laurent Cantet)

The Class (Dir. Laurent Cantet)

The surprise winner of this year’s Palme d’Or at the Cannes Film Festival was this deceptively simple tale of a French teacher (François Bégaudeau) at a state school in Paris.

The actual French title is ‘Entre Les Murs’ – which translates as ‘Between the walls’ – which is apt as the film never (apart from one shot at the beginning) strays outside the confines of the school.

Adapted from the 2006 novel of the same name by Bégaudeau, which in turn was based on his own real life experiences teaching in a Paris school, it is a rich and deeply satisfying film.

Not only did it scrupulously avoid the cliches that can plaue films set inside schools, but also managed to offer a plausible snapshot of modern French society by focusing tightly on a class of pupils and their teachers.

Although it is shot in the widescreen aspect ratio of 2:35, the camera hangs tight on each character and never really gives us a look at the French city landscape.

This might sound claustrophobic, but makes the lessons and world inside of the school (the staff room, the corridors, the playground) all come alive in an unexpectedly thrilling way.

Performances – especially from Bégaudeau and a very special cast of non-professional teenagers – were outstanding but the film also had a tremendous sense of humanity to it without ever slipping into cheap sentiment.

An example of a rare film that touches the heart whilst engaging the brain, The Class is a gem that I would urge anyone to go and see when it gets released in the UK in February.

[The Class is out at UK cinemas on Friday 27th February]

The Dark Knight (Dir. Christopher Nolan)

The Dark Knight (Dir. Christopher Nolan)

The most commercially successful film of the year (globally at least) was also one of the best, as this Batman sequel transcended its comic book origins to become one of the most ambitious blockbusters in years.

When Batman Begins came out in 2005, it was an impressive reinvention of the DC Comics character but I wasn’t as blown away as some were. But props to the suits at Burbank for recruiting a director like Christopher Nolan who had already made his mark with Memento in 2000.

The realistic approach to the Bruce Wayne character and Gotham City worked well and reaped dividends with this sequel, which built on the first film but also made for a richer experience.

Managing to transcend the usual limitations of the comic book genre, its ambitious approach owes more to crime epics like Heat and The Godfather than the usual summer comic book adaptation.

The story, set in a Gotham City soaked in crime, violence and corruption, revolved around three central characters: Bruce Wayne (Christian Bale), a billionaire vigilante dishing out justice at night time; Harvey Dent (Aaron Eckhart), the District Attorney boldly taking on organised crime; and The Joker (Heath Ledger), a mysterious psychopathic criminal wreaking havoc on the city.

Nolan and co-screenwriter Jonathan Nolan (with story credit by David S Goyer) crafted a spectacularly ambitious summer blockbuster with the different narrative strands developed in engrossing and genuinely surprising ways – at times it was so layered that key sequences often had parallel consequences.

As for the action, it follows the script in being similarly dense, and some of the big set pieces – especially two key sequences – have an unpredictable and chaotic quality to them, which is refreshing for this kind of genre.

The performances too were a revelation for a genre movie: Bale continues his solid work from the first film but Ledger and Eckhart brought much more to their roles than some might have expected.

As The Joker, Ledger managed to completely reinvent an iconic character as a wildly unpredictable psychopath who brings Gotham to it’s knees. Although – due to his tragically early death – there was always going to be added interest in his performance, he really was outstanding in creating a villain who is scary, funny and unpredictable.

Overall the technical contributions were outstanding – of particular note were Wally Pfister’s cinematography, Nathan Crowley’s production design and Lee Smith’s editing.

Special mention must also go to the diverting score by Hans Zimmer and James Newton Howard, which thankfully will be up for Oscar consideration after initially being barred due to a technicality.

Many aspects of the film raised interesting questions and parallels. Can we see Batman – a sophisticated force for good caught up in a moral dilemma – as a metaphor for the US military? Could The Joker – a psychopathic enigma wreaking terror on society – be a twisted version of Osama Bin Laden?

The fact that a comic book adaptation subtly provoked these points was daring and clever but also true to the darker comic books – especially The Killing Joke – that influenced on the film.

Although Ledger is almost a forgone conclusion for Best Supporting Actor – for both valid and sentimental reasons – the film itself might find more nominations in the major categories, which when you think about it speaks volumes to its quality.

[The Dark Knight is out now on DVD]

The Visitor (Dir. Thomas McCarthy)

The Visitor (Dir. Thomas McCarthy)

Tom McCarthy made one of the best films of 2003 with The Station Agent and his second film was just as good.

The story involved a college professor (Richard Jenkins) who finds a young immigrant couple living in his New York apartment and then follows the characters as they connect with one another in unexpected ways.

Like his previous work, it is thoughtful, beautifully observed and features rounded characters who feel like people you might actually meet in real life.

Jenkins is a character actor you might recognise – he’s probably best known for his fine work as Nathaniel Fisher in Six Feet Under or as the FBI agent in Flirting with Disaster.

Here he is finally given a lead role that allows him demonstrate his considerable acting skills and there is fine support too from Haaz Sleiman, Danai Jekesai Gurira and Hiam Abbass.

But what really made this stand out is the way it managed to tackle some really big themes with intelligence and grace: immigration, loss and love are just a few of the issues dealt with here but the approach was never stodgy or patronising.

Instead, it managed to take us deep into the hearts and minds of people caught up in the chilly climate of a post-9/11 world.

A rare film that manages to engage both the heart and brain, but does so with the subtle skill of a gifted director.

* Listen to our interviews with Richard Jenkins and Tom McCarthy about The Visitor *

[The Visitor is released on DVD in the UK on February 9th]

The Wrestler (Dir. Darren Aronofsky)

The Wrestler (Dir. Darren Aronofsky)

When I first heard about Mickey Rourke playing a has-been wrestler in a film directed by Darren Aronofsky I was intrigued.

Would it be similar to the director’s previous films like π and Requiem for a Dream? And what would Mickey Rourke be like in his first proper leading role for many years?

For Aronofksy it is a major – but welcome – departure in that it eschews many of the stylistic devices of his earlier work in favour of a raw, stripped down approach.

For Rourke it is nothing less than a triumphant comeback: a dream role that proves not only what a fine screen actor he can be, but also atones for the chaos of his professional career over the last 20 years.

The film itself is the story of a big time wrestler from the 1980s called Randy ‘The Ram’ Robinson, who has fallen on hard times and wrestles on the weekends in independent and semi-pro matches for extra money.

Health problems force him to re-evaluate his life which includes working in a deli, a possible relationship with a stripper (Marisa Tomei) and an attempted reconciliation with his estranged daughter (Evan Rachel Wood).

The parallels between Rourke’s own career and that of his character are there for anyone to see but there is more to the film than just brave casting: it paints a moving yet unsentimental view of outsiders struggling to make it in modern America.

The world of semi-pro wrestling is also brought to life with remarkable authenticity. Although the theatricality and hype of the WWF dominates the public perception of wrestlers, the realism on display in this story creates a much more authentic and poignant world.

A lot of the film’s charm rests on Rourke and Tomei, who play two contrasting characters who actually have much in common: both are performers who use their bodies and have problems reconciling their double lives.

Rourke is already being talked of as one of the frontrunners for the Best Actor Oscar and there is no doubt that he deserves recognition for what is one of the most memorable screen performances of the year.

[The Wrestler is out at UK cinemas on Friday 16th January]

WALL-E (Dir. Andrew Stanton)

WALL-E (Dir. Andrew Stanton)

Pixar continued their incredible run of form this year with yet another landmark animated film.

Set in a dystopian future circa 2815, it was about a waste disposal robot named WALL-E (Waste Allocation Load Lifter Earth-Class) who meets another robot named EVE (Extraterrestrial Vegetation Evaluator) and gets involved in an unlikely romance, as well as the future of the human race.

Directed by Andrew Stanton, it is probably the most visually impressive work Pixar have yet committed to film (and that is saying a lot) but it also resonated as a surprisingly moving love story.

Robots haven’t been this endearing since Silent Running and the two central characters are joy to watch – the boxy old school charm of WALL-E contrasting beautifully with the cool, sleek beauty of EVE.

Although I would never thought I would ever compare a Pixar movie to There Will Be Blood – both have startling opening sequences with little or no dialogue.

One of the clever aspects of the film is the casting of sound designer Ben Burtt as the central character – for those unfamilar with his work he was the pioneering sound editor on the Star Wars and Indiana Jones films.

Along with the animators, Burtt has helped create a character who is extremely expressive without using conventional language.

The same is true for EVE, so it is even more impressive that the filmmakers have managed to craft a compelling relationship between them.

The landcaspes were equally impressive, full of rich detail and nods to other sci-fi films.

* Listen to our interview with Angus MacLane, the directing animator of WALL-E *

[WALL-E is out now on DVD]

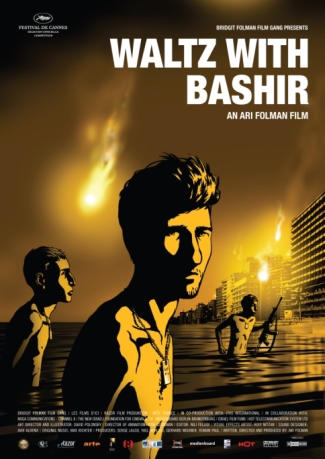

Waltz With Bashir (Dir. Ari Folman)

Waltz With Bashir (Dir. Ari Folman)

One of the most daring and original films was this astonoshing animated film about the 1982 Sabra and Shatila massacre and the memory of the Israeli soldiers involved in the invasion of Lebanon at the time.

Directed by Ari Folman, it examines his own experiences on that mission and the struggle to remember what happened when he interviews various army colleagues from the time.

The strange title is taken from a scene with one of Folman’s interviewees, who remembers taking a machine gun and dancing an ‘insane waltz’ amid enemy fire, with posters of Bashir Gemayel lining the walls behind him. (Gemayel was the Lebanese president who whose assassination helped trigger the massacre.)

Animation isn’t normally associated with historical and political films, but here it worked brilliantly creating some haunting and indelible images.

A hugely ambitious project, it took four years to complete and is and international co-production between Israel, Germany and France.

Another aspect which makes this story so intrguing is that the Israeli troops were not guilty of the massacre itself but of standing by and letting Lebanese miltia murder Palestinian refugees.

It is the memory of, or rather the inability to remember, this event that lies at the core of the story. Has Folman unconsciously blocked out the memory? Does guilt cloud any rational perspective?

The raw power of the source material is enhanced by some extraordinary imagery, with a remarkable and inventive use of colour for certain sections, especially those involving the sea.

Added to this is Folman’s narration which has an almost hypnotic effect when set alongside the visuals, almost as if the audience is experiencing a dream whilst watching the film itself.

Back in May it premiered to huge acclaim at Cannes and was one of the front runners to win the Palme d’Or. The film also won 6 Israeli Film Academy awards (including Best Picture) and looks likely to be a strong contender for the Best Foreign Film at the Oscars.

Much of that praise is richly deserved because this is an arresting and highly original film that deserves special credit for taking a highly politicised and contentious event and yet somehow makes a wider point about the futility of war.

The recent events in the Gaza strip only reinforce what a timely film this is but the central message about the horrors and futility of war has a relevance not just confined to the cauldron of the Middle East.

* Listen to our interview with Ari Folman about Waltz with Bashir *

[Waltz with Bashir is out on DVD in the UK on March 30th]

[ad]

HONOURABLE MENTIONS

[Rec] (Dir. Jaume Balagueró)

Appaloosa (Dir. Ed Harris)

Battle For Haditha (Dir. Nick Broomfield)

Blindness (Dir. Fernando Meirelles)

Burn After Reading (Dir. The Coen Brothers)

Changeling (Dir. Clint Eastwood)

Flight Of The Red Balloon (Dir. Hsiao-hsien Hou)

Funny Games US (Dir. Michael Haneke)

Gran Torino (Dir. Clint Eastwood)

Happy-Go-Lucky (Dir. Mike Leigh)

Hellboy 2: The Golden Army (Dir. Guillermo Del Toro)

Nick And Norah’s Infinite Playlist (Dir. Peter Sollett)

Religulous (Dir. Larry Charles)

Revolutionary Road (Dir. Sam Mendes)

Sugar (Dir. Anna Boden & Ryan Fleck)

The Curious Case of Benjamin Button (Dir. David Fincher)

The Reader (Dir. Stephen Daldry)

W. (Dir. Oliver Stone)

N.B. Have a look at my list of the best films from 2007 which has now been updated to include those that got a UK release in 2008. (They were Gone Baby Gone, Persepolis, The Orphanage, In Search Of A Midnight Kiss, Joy Division, My Winnipeg, Savage Grace, Shotgun Stories, Son Of Rambow, The Band’s Visit and The Mist).

What about you? Leave your favourites from this year in the comments below.

> Find out more about the films of 2008 at Wikipedia

> Check out more end of year lists at Metacritic

> Have a look at the Movie City News end of year critics chart

> Check out our best DVDs of 2008