Maurice Sendak’s 1963 children’s book has found its way to the screen and the result is an adaptation of rare depth and feeling.

For those unfamiliar with the source material, it is the story of a wild young boy named Max who is sent to his bedroom without his supper. His room grows into a forest and he sails off to a magical land where (as the title suggests) ‘the wild things are’.

Part of the charm and beauty of the book is how short and sweet it is, which inevitably presented any filmmaker a big challenge. How would you expand it to feature length and preserve its qualities?

After four decades of development hell (including some test footage shot years ago by John Lasseter) director Spike Jonze was given the onerous task of making the film.

There was plenty of speculation during the filming as to how Jonze was going to portray the creatures and rumours abounded that the director was at creative loggerheads with the studio brass.

The fact that the bulk of the shoot occurred in 2006, followed by extensive visual effects work last year in London, suggests that this was not the smoothest of productions.

But sitting down to watch the film, none of that mattered and Jonze and his team have come up with a bold and expansive treatment of the book, which not only captures Sendak’s emotional tone but even takes it to another place.

The opening scene sets things up perfectly with a hand-held camera capturing a burst of Max (played by newcomer Max Records) being wild inside his home before the real action begins.

This extended prologue might give fans of the book pause for thought – we actually see his mother (Catherine Keener) and family – but in the context of the expanded narrative it doesn’t jar.

But it is with the wild things that the film really comes alive. It would have been an option to completely render them with CGI but the decision to use actors inside suits with visual effects replacing their faces was inspired.

Casting is also key to why the movie works: Records is not a typical child actor, with a raw quality that fits just right whilst the voice cast is every bit as good.

The casting of James Gandolfini as Carol (the wild thing Max becomes closest to) brilliantly plays off his Sopranos persona, highlighting his joy, vulnerability and anger.

Chris Cooper, Lauren Ambrose and Paul Dano also chip in with excellent vocal performances, making their characters as varied and complex as they should be.

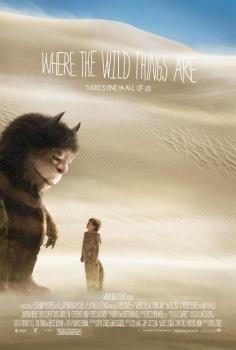

The Australian locations, beautifully captured by cinematographer Lance Acord, also add a visual richness to the film which wouldn’t have been the same if done on green screen soundstages.

Some adults may complain that Jonze has made a children’s film that slants towards to older audiences, but this is exactly what makes the film special.

Instead of sugar coating the story and patronising the viewer, he has (along with co-screenwriter Dave Eggers) treated the source material and cinema audience with the respect they deserve.

There is something other worldly and anarchic about this film project and in some ways I’m staggered it actually got made like this.

However, its mix of humour, heart and imagination could make it as beloved as the book, for audiences today and many years to come.